Reproductive Justice Media Reference Guide

In the past 20 years, movements fighting for justice have changed in the U.S. As younger people join the struggle, as racial demographics shift in the U.S., and as campaigns and groups seek to link across issue and advance systemic change—movements for progressive change have evolved in many ways. The story is not just about an incorporation of new technology or the tension between activist generations—it is also a story about how movements are reimagining their focus, frame, and narrative.

Mainstream media coverage of reproductive health and rights has historically tended to focus on a single “choice” framework or on legislation and litigation surrounding abortion and birth control. As a result, reporting may rely on the same small pool of organizational spokespeople, primary healthcare providers, and legal analysts. The very public controversy around the legal right to abortion has limited the media coverage of many other reproductive rights and health issues.

Today, journalists have an opportunity to shed new insight onto an “old” story. Rather than exploring familiar terrain about abortion rights, or the latest legal maneuvering, journalists have a chance to find a new angle and to tell the story about the work being done by reproductive justice activists to expand access, introduce new issues to the reproductive health and rights framework, and to advance meaningful political and social change.

As a national network of more than 150 organizations working at the local, state, and national levels to advance the rights, recognition and resources of all families, Strong Families is uniquely positioned to see the reproductive justice (RJ) issues facing different kinds of families—from LGBTQ to immigrant families and many other kinds of families. Strong Families defines reproductive justice (RJ) as all people having the social, political, and economic power and resources to make healthy decisions about their gender, bodies, sexuality, and families for themselves and their communities. Because the definition is broad, the issues that fall under the RJ umbrella are equally broad. From abortion access to the rights of incarcerated individuals and resources for young families, RJ issues run the gamut. The picture is broad and complex, as just a few data points show.

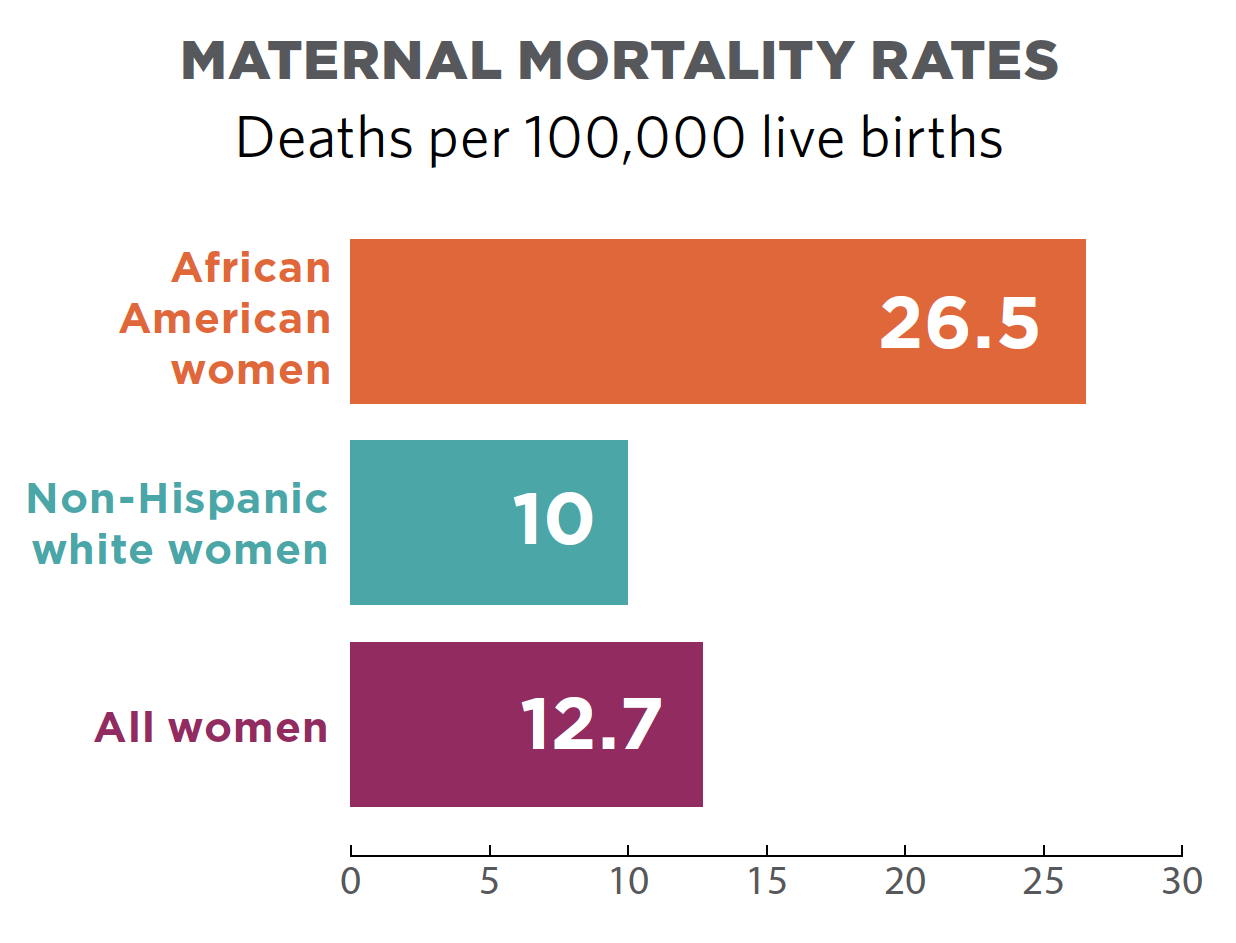

- Maternal mortality rates are over three times higher among African American women, at 21.5%, compared to non-Hispanic white women at 6.7% and 9.2% of women of other races.1

- Vietnamese-American women have the highest cervical cancer rate of any ethnic group, five times the rate of non-Hispanic white women.2

- Racial disparities exist for same-sex couples: Black female same-sex couples have a median income of $21,000 less than white female same-sex couples.3

But RJ is not merely a set of depressing statistics and terrible facts. Rather, it is both an analytic framework and a social movement for self-determination. RJs approach makes clear that reproductive health and choices must be contextualized and that voices that traditionally have been marginalized are critic ofallal to defining the problem, posing solutions, and leading the movement for change.

Members of the media have a substantial influence on the public’s attitudes toward and understanding of RJ issues. In covering stories about reproductive health and rights, journalists can ask three questions to explore the possible RJ implications:

- Are people of color, young people, immigrants, LGBTQ individuals, or low-income communities being disproportionately affected in a way that warrants exploration? Are certain communities or populations experiencing a significant difference in outcomes than others?

- Who are the experts from communities affected by the disparity who can serve as sources or provide first-hand perspective for the story?

- What are the historic and systemic factors that contribute to these outcomes? In many instances, law and policy, intervention from the medical establishment, or legacies of racism and colonialism have created disparities that provide critical context in understanding today’s outcomes.

This Strong Families media guide is intended to be used by a variety of traditional and new media outlets seeking to learn about or expand their knowledge of RJ in their writing. It is not intended to be an all-inclusive encyclopedia of issues within RJ, nor is it intended to limit coverage to the issues highlighted herein.

With the 42nd anniversary of Roe v. Wade in 2015, our first RJ In Focus looks at abortion, in part due to renewed state-level attacks on access to abortion, and increased coverage of reproductive rights in the media. Upcoming guides in 2015 will include suggested best practice reporting on criminalization and incarceration, young parents, and queer and trans youth.

Reproductive Justice In Focus: Abortion

Abortion Data

With the 42nd anniversary of Roe v. Wade in 2015, our first media guide focuses on abortion, in part due to renewed state-level attacks on access to abortion, and increased coverage of reproductive rights in the media.

Basic facts on abortion in America:

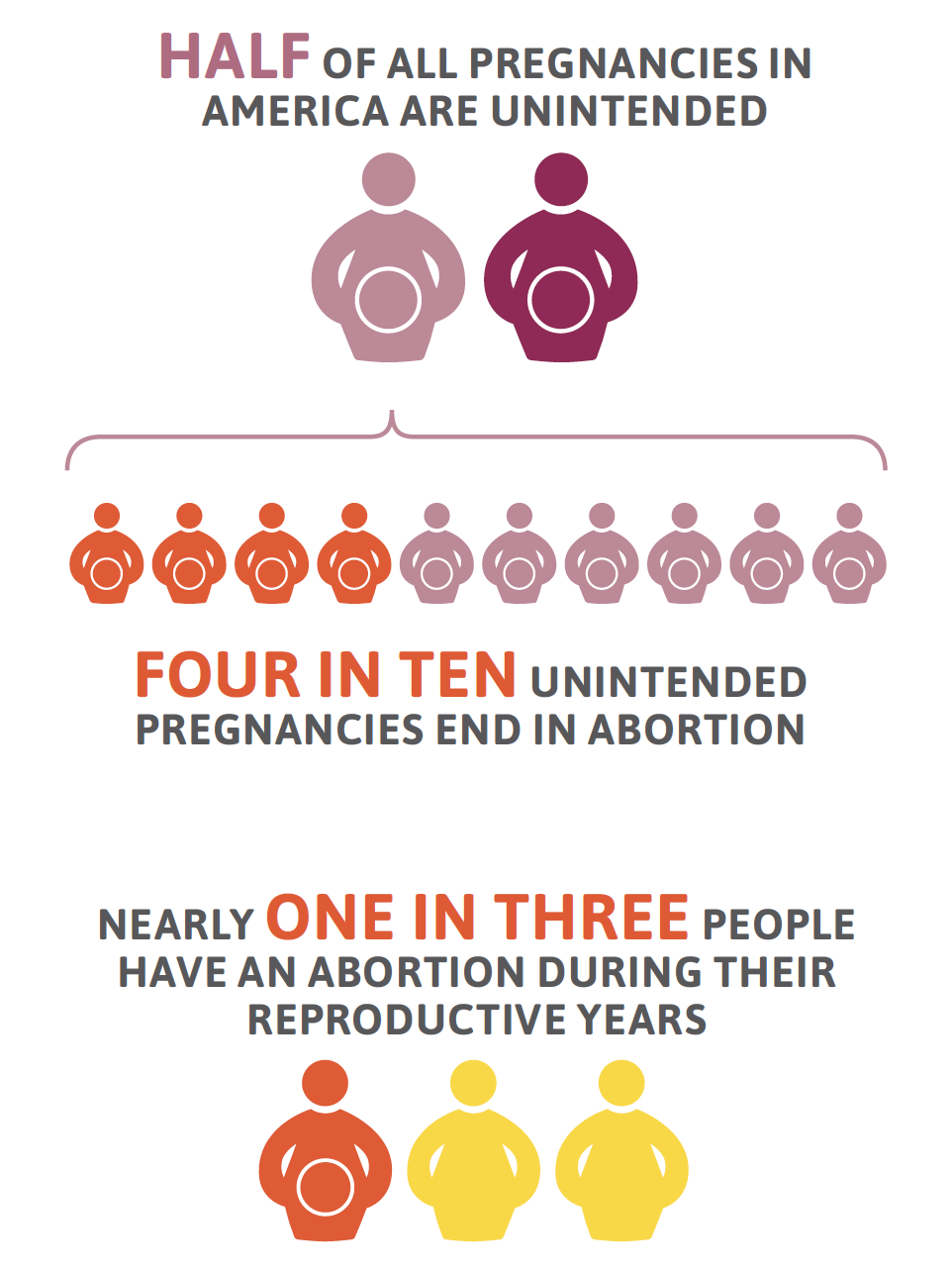

- Half of all pregnancies in America are unintended. Four in ten unintended pregnancies end in abortion, and nearly one in three women have an abortion during their reproductive years.4,5

- Abortion rates are currently at their lowest since the U.S. Supreme Court legalized the procedure in 1973, and studies suggest that a primary reason is increased use of new, long-acting reversible contraceptive methods (LARCs)—such as IUDs or contraceptive implants—that are helping to significantly reduce unintended pregnancies.6 Between 2008 and 2011, abortion rates fell by nearly 13%.7

- Abortion rates continue to drop among young people. In 2008, 7% of all abortions were obtained by minors (those younger than 18).8

- Women who want to get an abortion but are denied are three times more likely to fall into poverty than those who can get an abortion.9

- Women with lower socioeconomic status—specifically those who are least able to afford out-of-pocket medical expenses—already experience disproportionately high rates of adverse health conditions. Denying access to abortion care only exacerbates existing health disparities.10

- Twenty-seven percent of women obtaining abortions have incomes between 100-199% of the federal poverty level.11

On Gender and Abortion

Throughout this section, we incorporate gender-neutral language to discuss abortion. In other words, where possible we say “a pregnant person,” rather than “a pregnant woman.” We do this because transgender men and gender non-conforming people can also be pregnant.

At the same time, most data collection methods offer limited gender self-identification options and nearly all statistics on pregnancy and abortion refer to “women” exclusively. In addition, we recognize that using gender-neutral language can mask the disproportionate impact of anti-abortion policies on women, institutionalized sexism, and the many efforts to undermine the self-determination and autonomy of all women, including transgender women.

Roe v. Wade: Legal Rights But Limited Access

In the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, the U.S. Supreme Court found that women, in consultation with their physicians, have a constitutionally protected right to abortion before viability (estimated at around 24 weeks gestation12) free from government interference. Despite this groundbreaking decision, many women in the United States have never had true access. State-level policies such as mandatory waiting periods, exclusion of abortion coverage in Medicaid and other health insurance plans, parental involvement laws, targeted regulation of abortion providers (known as TRAP laws) and similar barriers disproportionately affect young women and low-income women or rural communities by limiting their ability to find and afford safe and legal abortion.

At the federal level, since its initial passage of the Hyde Amendment in 1976, Congress has repeatedly denied insurance coverage for abortion in federally-funded health programs, withholding most coverage from people who qualify for such programs: Medicaid-eligible individuals and Medicare beneficiaries; military families; federal employees and their dependents; Peace Corps volunteers; Native Americans; women in federal prisons and immigration detention centers; and residents of the District of Columbia.

Reproductive justice advocates understand that a right is in name only if those who need that right don’t have meaningful ability to exercise it. Reporting on Roe should include the ways that this right is being whittled down and the impact on diverse communities.

Not Preferred: Roe v. Wade guaranteed women the right to an abortion.

Preferred: Roe v. Wade granted the right to legal abortion before viability, though Congress and state legislators have been allowed to restrict access to the procedure, disproportionately affecting people of color or those who are living in rural areas.

Public Opinion on Abortion

Like the movement for reproductive justice, a new generation of supporters are emerging around abortion rights and access. Millennials and people of color are supportive of abortion rights and access, including:

- 56% of millennials believe that abortion should be legal in all cases, higher than those born between 1965–1980 when Roe v. Wade made abortion legal.13

- 67% of African Americans believe that Roe v. Wade should not be overturned.14

- 76% of African Americans believe that health insurance should cover abortion.15

- Latino support for abortion access is growing. Among likely Latino voters in Texas, 78% agree that women have the right to make their own decisions about abortion without politicians interfering.16

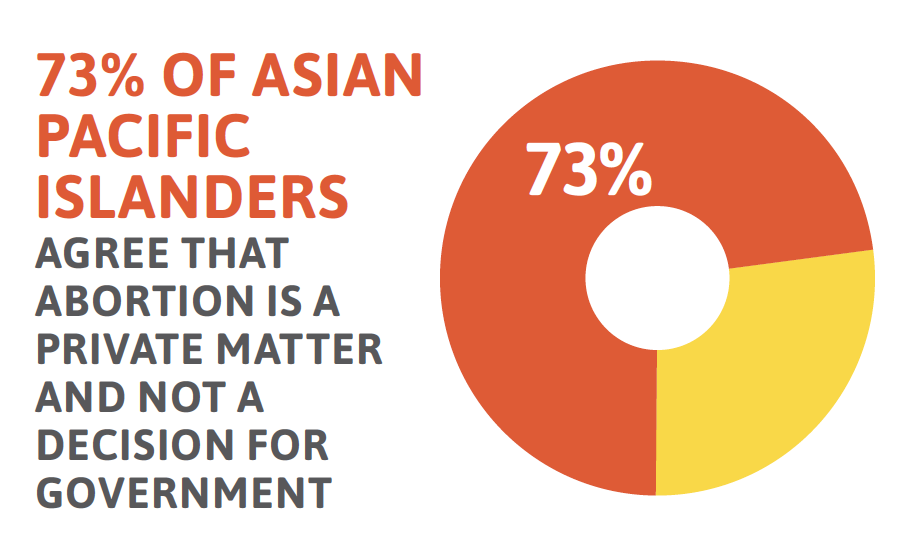

- 73% of Asian Pacific Islanders agree that abortion is a private matter and not a decision for government.17

Both those seeking to limit abortion access and reproductive health champions use polling to articulate where public sentiment lies. Reporters can dig beneath the data being presented by comparing questions across polls paid for by different groups, by looking at polling over time, and by articulating the margin of error clearly for readers.

Some recent polls about abortion access and public opinion include:

- Apoyo y Respeto (Support and Respect): Texas Latin@ Voters Attitudes on Abortion (2014)

- African American Attitudes on Abortion, Contraception, and Teen Sexual Health (2013)

- Millennials of Color Poll on Abortion Access (2012)

- Latino Voters Hold Compassionate Views on Abortion (2012)

- Religion, Values, and Experiences: Black and Hispanic American Attitudes on Abortion and Reproductive Issues (2012)

Shame, Stigma, and Reproductive Health

While abortion is the most common gynecological procedure that women experience,18 societal beliefs about the “proper” role of women and women’s sexual behaviors may result in shame and stigma. Individuals who have had an abortion may face judgment from others, isolation, self-judgment and community condemnation.19,20

Other circumstances can bring on similar feelings of shame and stigma, such as being a young parent, having a sexually transmitted infection (STI), or expressions of sexuality and gender identity. Reporters covering RJ issues like these have an opportunity to share the wider context of individual lives as well as important health data that helps readers understand both in a way that can curb unnecessary judgment, while also reporting the facts.

Not Preferred: She had a sexually transmitted disease.

Preferred: Like more than 1 in 3 people in the U.S., she had a sexually transmitted infection.21

The Hyde Amendment and Other Funding Restrictions

Medicaid is a health insurance program for low-income people who meet certain eligibility criteria. Though Medicaid covers a range of prenatal and postnatal care, Congress prohibits Medicaid from covering abortion in nearly all circumstance and it is the only medical procedure banned in the Medicaid program in this way. The Hyde Amendment, first passed in 1976 (just three years after Roe) and renewed annually in the federal appropriations process, prohibits federal funding for Medicaid coverage of abortion care except when pregnancy is a result of rape or incest or when her pregnancy endangers her life.

Over nine million women of reproductive age—nearly one in seven—are insured by Medicaid.22 However, because of broader social and economic disparities and existing inequalities around gender, race, and income, restrictions on Medicaid coverage of abortion disproportionately impact women of color, particularly Black and Latina women.

Hyde has far reaching consequences beyond the nine million women insured through Medicaid. It also impacts:

- Indian Health Services, the health-service delivery system for approximately two million American Indians and Alaska Natives, which receives funding from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Immigrant individuals, who are excluded from receiving Medicaid altogether.

Denial of abortion coverage has a profoundly harmful effect on women and families, particularly those already struggling to make ends meet. A woman who attempts to access abortion services but is denied, is three times more likely to fall into poverty than a woman who is able to get the care she needs. People may be forced to make impossible decisions: between keeping keeping the lights on or paying for needed healthcare. For others, cost is an ultimately insurmountable barrier. One in four low-income women who seek abortion care are unable to afford to pay the out-of-pocket cost and are forced to carry the pregnancy to term.23 These hardships fall hardest on people of color, who are more likely to live in poverty and participate in federally-funded health programs.

Reporting on the cost of abortion and its accessibility should include the impact of the Hyde Amendment and what it means that politicians deny women Medicaid for medically necessary coverage.

Not Preferred: Hyde is the law of the land; there is no taxpayer funding of abortion, and government funding of abortion is banned.

Preferred: Hyde denies Medicaid coverage of abortion; federal funds are withheld from covering a woman’s abortion; Congress currently denies Medicaid insurance from covering abortion.

Race and Abortion

Reporting on racial inequities in who obtains abortion services without exploring the larger context often leads to inaccurate stories that perpetuate myths and stereotypes about communities of color, particularly Black and Latina women.

Women of color are regularly targeted for scrutiny and policing of their reproductive health decisions by both policy makers and popular culture. Examples include the billboard campaign targeting Black and Latina women, or sex-selective abortion bans that target Asian and Pacific Islander (API) women in the U.S.

Journalists should avoid attempting to describe the “types” of individuals who have abortions or speculating about the cultural reasons why some groups obtain them more than others. Rather, reporting can include background information on the many factors and circumstances which contribute to an individual’s decision about an unintended pregnancy as well as relevant data on income and healthcare access, while avoiding stereotypical traps by referencing sexual behavior or decision making.

Not Preferred: While overall rates of abortion are declining in the U.S., rates for Black and Latina women remain higher than abortion rates for all other women.

Preferred: Black and Latina women are more likely to have low-incomes and limited access to preventive healthcare, including regular access to birth control, which contributes to their higher rates of abortion.

Youth Access to Abortion

Public discussions of abortion and the women who have them often focus on adolescents, creating the impression that most abortion patients are teenagers. Trends in reporting about teen pregnancy often reinforce these misguided but popular stereotypes. In reality, 2008 data shows that adolescents (women younger than 20) accounted for 18% of abortions, but that only 7% of abortions were obtained by minors (those younger than 18).24

Pregnancy rates among young people—across all ethnicities and races—have fallen by nearly 50% since the 1990s.25 These dramatic drops are due primarily to young people’s improved birth control access and use.

Even with increased birth control use, nearly 82% of all pregnancies among young people are unintended. Nearly 1 in 4 young women at risk for unintended pregnancy was not using any contraceptive method at last intercourse.26

From a policy-making perspective, adolescents and minors in particular, face among the harshest restrictions in accessing abortion services. As of May 2014, laws in 38 states require a minor seeking an abortion to involve parents in the decision.27

Given that the procedure is relatively rare, reporters should delve into the complexities young people may face that would require that they have the ability to access safe and confidential abortion care. Reporting on young people’s access to abortion should take into consideration the rarity of a person under 20 seeking the procedure while highlighting the circumstances under which they do—painting a more accurate picture of the realities young people are facing and the agency they employ within them.

Immigrant Communities and Abortion

Immigrant women make up 13% of the total female population in the U.S.,28 yet this group experiences some of the most persistent barriers to comprehensive reproductive healthcare services.

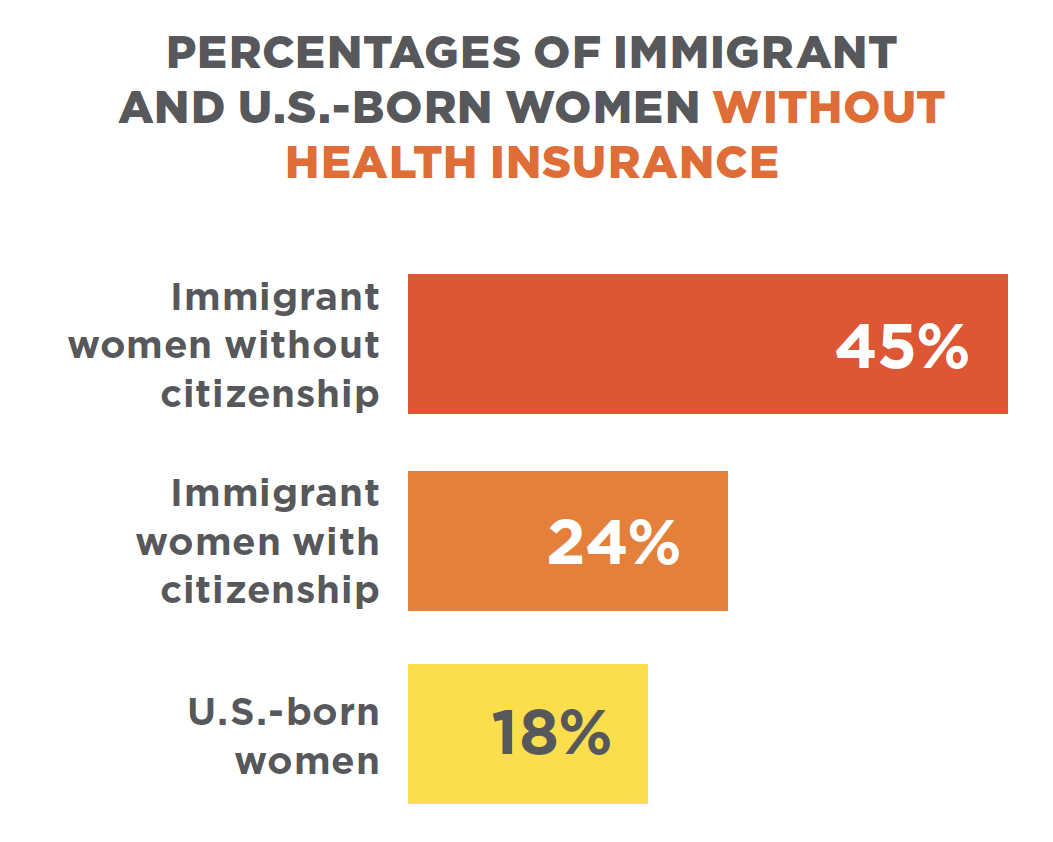

By far the most significant barrier for immigrants is the low rates of insurance coverage in immigrant communities. Despite the fact that immigrant women have nearly the same labor force participation and employment rates of non-immigrant women, they have significantly less access to employer-sponsored health insurance coverage.

Immigrant women are more likely to work in low-wage sectors of the economy, including service and agriculture, and for small firms, which are less likely to offer health coverage to their employees. A significant portion of those who will remain uninsured after implementation of the Affordable Care Act are immigrants, due to restrictions on immigrant eligibility for its expanded coverage options.

Immigrants face added barriers to abortion access, including: lack of affordable insurance options, poverty, lack of culturally and linguistically appropriate care, fear of apprehension by immigration enforcement, and bans on abortion access for women being held in immigration detention.

Because immigrants are as diverse a group as any, reporters should steer clear of writing about immigrant communities as if they are from one region, religion, or cultural background and note the wide range of immigration “statuses” and consequently the disparate healthcare options afforded different populations.

Opposition

A network of national and state level organizations focus on undermining access to abortion. These groups include: the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), Americans United for Life, Family Research Council, National Right to Life, National Pro-Life Alliance, and the Susan B. Anthony List, which supports candidates who are opposed to abortion.

These groups have launched an unprecedented attack on abortion access and affordability, and more than 282 abortion restrictions have been enacted since 2010. During the first quarter of 2015, more than 332 bills intended to restrict access to abortion were introduced at the state level.

In addition to policy-oriented groups, radical anti-choice groups like Operation Rescue, Live Action, and the Center for Medical Progress engage in deceptive and misleading campaigns using undercover video, surveillance, and sting operations to undermine abortion providers and to stimulate outrage amongst conservative legislators to further restrict access to abortion.

The increasingly hostile policy climate and in-your-face actions of radical anti-choice groups creates a climate where threatening and targeting of abortion providers and abortion clinic staff can thrive. In a recent study of national clinic violence, over 50% of clinics report threatening and intimidating behaviors including wanted style posters, leaflets featuring doctors’ photographs and home addresses, and aggressive blockades.

Many anti-abortion policy and radical anti-choice groups also cite discredited or misrepresented research on the impact of abortion on women. However, exhaustive reviews by panels convened by the U.S. and British governments have concluded, for example, that there is no association between abortion and breast cancer. There is also no indication that abortion is a risk factor for other cancers. Claims of depression or other emotional distress caused by an abortion have also been widely disputed by medical authorities who find these effects can be attributed primarily to the impact of shame and stigma on those who have had an abortion, rather than the procedure itself. Taking medically inaccurate claims at face value and comparing them without context to medically sound arguments simply to have a “balanced” perspective is not responsible journalism.

Not Preferred: pro-choice, pro-abortion rights

Preferred: reproductive health advocates, supporters of abortion access

Not Preferred: pro-life, anti-abortion, right to life

Preferred: those seeking to restrict abortion

Appendix

Terminology

Abortion: A medical procedure used to end pregnancy. There are different methods of abortion commonly performed depending on length of pregnancy. One is through a medication and the other methods are procedures that take place in a clinic, including aspiration (the most common method) and D&E (dilation and evacuation).30

Fetus: A fetus is defined from 8 weeks after conception until term while in the uterus.31

Late Abortion: Late abortion refers to abortion procedures done after fetal viability. The vast majority of states restrict late-term abortion access, including 21 states that impose prohibitions after fetal viability. Opponents to reproductive health and rights often refer to all late-term abortions as “partial birth abortions,” a medically inaccurate and skewed term.

Medication Abortion: An abortion using the medication mifepristone and misopristol prescribed by a medical provider. Medically induced abortion can be done during the first two months of pregnancy.32

Surgical Abortion: There are several forms of surgical abortion. The most common type of surgical abortion in the U.S. is done by aspiration. Surgical abortion is performed in a clinic or hospital, and can be used up to 16 weeks after the last period.33

TRAP Laws: Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers. Common TRAP regulations include those that limit the provision of care only to doctors; require doctors to convert their physical office into mini-hospitals at great expense; limit abortion care to hospitals or other specialized facilities; and/or require doctors to have admitting privileges at a local hospital with nothing requiring facilities to grant such privileges. 45 states and the District of Columbia have laws subjecting abortion providers to burdensome restrictions not imposed on other medical professionals.34

Unintended Pregnancy: A pregnancy that is mistimed, unplanned, or unwanted at the time of conception.35

Viability: Roe v. Wade developed a trimester framework for gestational age, and declared that abortions in the third trimester could only be performed if the health of the mother was in jeopardy, implying that a fetus was legally viable at 28 weeks. Since Roe passed, the legal definition of viability has been delegated to individual states. States often rely on the attending physician to determine viability, for those states that define viability, the limit ranges from 19 to 28 weeks.36

Endnotes

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2012, June). Infant, neonatal, and maternal mortality rates by race: 1980 to 2007. In Statistical abstract of the United States.

- National Asian Pacific American Women’s Forum. (2009). HPV, cervical cancer, and API women: Eliminating health disparities.

- National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute & National Black Justice Coalition. (2000; 2005). Black same-sex households in the United States.

- Guttmacher Institute. (2014, July). Fact sheet: Induced abortion in the United States.

- Jones, R. K., & Kavanaugh, M. L. (2011). Changes in abortion rates between 2000 and 2008 and lifetime incidence of abortion. Obstetrics & Gynecology 117(6), 1358–1366.

- Somashekhar, S. (2014, February 2). Study: Abortion rate at lowest point since 1973. Washington Post.

- Guttmacher Institute. (2014, July). Fact sheet: Induced abortion in the United States.

- Jones, R. K., Finer, L. B., & Singh, S. (2010). Characteristics of U.S. abortion patients, 2008. New York: Guttmacher Institute.

- Foster D. G. (2012, October), Socioeconomic consequences of abortion compared to unwanted birth, American Public Health Association annual meeting.

- Ibid.

- Guttmacher Institute. (2014, July). Fact sheet: Induced abortion in the United States.

- American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2012, June 18). Most obstetrician-gynecologists understand fetal viability as occurring near 24 weeks gestation, utilizing Last Menstrual Period dating.

- NPR.org. (2014, March 10). 4 Reasons the Pew Millennials Report should worry Democrats, too.

- PublicReligion.org (2012, July 26). The African American and Hispanic Reproductive Issues Survey.

- Belden Russonello Strategists, LLC. (2013, February). African-American attitudes on abortion, contraception and teen sexual health.

- National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health. (2014, October 22). Latino voters in Texas and abortion: Results from a statewide survey of Latino likely voters.

- Ramakrishnan, K., Lee, T., (2013, April). Where do AAPIs stand on critical issues? National Asian American Survey

- Kumara, A., Hessinia, L. & Mitchell, E. M. H. (2009, February). Conceptualising abortion stigma. Ipas, North Carolina, USA; Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Biostatistics, and Bioinformatics, Amsterdam Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- Cockrill, K., Upadhyay, U. D., Turan, J., & Foster, D. G. (2014, June). The stigma of having an abortion: Development of a scale and characteristics of women experiencing abortion stigma. Perspectives on Reproductive and Sexual Health, 45(2), 79–88.

- Ibid.

- US News and World Report. (2013, February). More than 100 million Americans have an STD: Report. HealthDay.

- All* Above All & Ibis Reproductive Health. (2014, August). Research brief: The impact of Medicaid coverage restrictions on abortion.

- Henshaw, S.K., Joyce, T., Dennis, A., Finer, L., and Blanchard, K. (2009) Restrictions on Medicaid Funding for Abortions: A Literature Review. New York: Guttmacher Institute.

- Jones, R. K., Finer, L. B., & Singh, S. (2010). Characteristics of U.S. abortion patients, 2008. New York: Guttmacher Institute.

- Guttmacher Institute. (2014, May). Fact sheet: American teens’ sexual and reproductive health.

- Mosher, W. D., & Jones, J. (2010), Use of contraception in the United States: 1982–2008. Vital and Health Statistics 29(23).

- Guttmacher Institute. (2014, May). Fact sheet: American teens’ sexual and reproductive health.

- American Immigration Council, Immigration Policy Center. (2014, September). Immigrant women in the United States: A portrait of demographic diversity.

- Guttmacher Institute. (2014, July). Fact sheet: Induced abortion in the United States.

- 1 in 3 campaign.(n. d.).

- Barfield, W. D. & the Committee on Fetus and Newborn. (2011, July 1). Clinical reports: Standard terminology for fetal, infant, and perinatal deaths. Pediatrics 128, 177–181.

- 1 in 3 campaign.(n. d.).

- Ibid.

- TRAP Laws. (n. d.).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n. d.). Unintended pregnancy prevention.

- Arzuaga, B., & Lee, B. H. (2011, December). Pediatrics perspective: Limits of human viability in the US: A medicological review. Pediatrics 128(6),1047–1052.

Who Made This Tool?

Strong Families is staffed and led by Forward Together. This Reproductive Justice Media Guide was created by the following Strong Families leaders:

- Advocates for Youth

- Forward Together

- Illinois Caucus for Adolescent Health

- National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health

Groups that assisted in the creation of this guide include:

Direct media inquiries for Strong Families to Kalpana Krishnamurthy at kalpana@forwardtogether.org.

To learn more about all the diverse reproductive justice groups that are part of the Strong Families movement, click here.