We Keep Each Other Safe

A Guide By and For Black, Indigenous, Latinx, POC and LGBTQ Communities Navigating the COVID-19 Pandemic

Forward Together worked with our partners The Committee of Interns and Residents and Last Mile to create the guide “We Keep Each Other Safe” to acknowledge the uneven and unsafe structures that we must navigate every day when seeking healthcare. This guide is designed by and for our communities to help us keep each other safe during the pandemic and to support all of us in getting the best care possible if any of us or any of our loved ones become sick with COVID-19.

English | Español

Introduction

We put this guide together to acknowledge the uneven and unsafe structures and institutions that people of color, immigrants, Indigenous people and queer and trans people engage with every day and to provide necessary support in that context. As the country reopens and throughout the pandemic, this information is critical for our communities.

This guide is designed by and for our communities to help us keep each other safe during the pandemic, to make sense of and spread important information coming out about COVID-19, and to support all of us in getting the best care possible if any of us or any of our loved ones become sick with COVID-19. By keeping this information on hand and by giving us your feedback on the guide, you are making a safer world for all of us.

The Three Most Important Guidelines: MAD! (Mask + Air + Distance)

Mask! Wear a mask that fully covers your mouth and nose.

Air! Keep indoor air fresh. Open windows to get outdoor air flowing through the space.

Distance! Stay at least 6 feet (2 meters) apart from others. You are at a higher risk of getting COVID-19 if you work indoors or live in a multi-occupant home or building.

The new coronavirus is affecting Black people, Indigenous people, Latinx people, undocumented immigrants and queer and trans people in different ways in comparison to white, heternormative communities, as wells as across and within our communities. We can see the first difference in the disproportionate rates of infection and mortality our communities are experiencing during the pandemic compared to white people. Systemic injustice in our society continues to create greater overall risk of health complications, now additionally as a result of COVID-19, for our people. Our communities are more likely to be pushed and trapped into poverty and denied access to adequate medical care, paid medical leave, and basic necessities — and these harms and abuses against us have increased during this pandemic. While our communities share characteristics that collectively make us the targets of racism, colonialism, and xenophobia, we also face unique challenges in staying safe during a global pandemic. Understanding the specific ways this disease is interacting with systemic injustice and affecting our distinct and overlapping communities is important in limiting the harm we experience.

Because of deep and widespread systemic racism and white supremacy across social services and public and private institutions, Black and Latinx people are three times more likely to become infected and hospitalized compared to their white counterparts, and nearly twice as likely to die from the virus as white people.1 That means for every 10 white patients that become hospitalized because of COVID-19, 30 Black and 30 Latinx patients are hospitalized.

While rates of COVID-19 infection for Indigenous people vary widely across different Native American reservations, the historic and present-day impacts of colonialism and genocide continue to cause amplified harm for Indigenous communities as a whole. Some reservations have much greater infection rates than the general U.S. population. In New Mexico, Native people make up around 10% of the state’s population, but more than 55% of its COVID-19 cases.2

Rates of COVID-19 infection for Indigenous people vary widely across different Native American reservations. Some reservations have much greater infection rates than the general U.S. population. In New Mexico, Native people make up around 10% of the state’s population, but more than 55% of its COVID-19 cases.

The government has not collected detailed data on LGBTQ people and COVID-19. Therefore, it is difficult to really understandthe extent of the problem LGBTQ people are navigating. We do know that COVID-19 is particularly dangerous for LGBTQ adults. Unsafe and harmful social and healthcare systems have long contributed to higher rates of chronic conditions like cardiovascular disease, obesity, cancer and HIV/AIDS in LGBTQ communities. When combined with COVID-19, these underlying health conditions put LGBTQ communities at higher risk. We also know that COVID-19 in combination with discrimination and isolation has serious implications for LGBTQ youth and their mental health. 3

I had COVID-19 in April of this year. I started experiencing shortness of breath but paid it no mind. I was feeling out of breath with even a short walk to my car. When I spoke, I sounded like someone having an asthma attack. I have a tendency to overlook my health when things get busy, but my symptoms were so severe that I finally called my doctor. As soon as she heard my wheezing, she instructed me to go to the emergency room. Until that moment, I hadn’t taken my symptoms seriously, and the urgency in her voice finally gave me the permission to make my health a priority. When I arrived at the hospital, I was taken in, tested and given an X-ray. Fortunately, I didn’t need to be hospitalized. I was discharged and spent the next several weeks quarantining in my home, trying to avoid passing the virus on to my family.

The coronavirus should be taken seriously. I urge you not to wait until your symptoms are so severe, like mine were, that you can barely breathe.

Folks who come from Black, Latinx, Indigenous, immigrant, LGBTQ or poor communities, may have a tendency to delay our care. That might be because of a lack of access to care, past negative experiences with medical professionals or a mistrust of the healthcare system. All of those responses are understandable given our histories and individual experiences around our healthcare. But the coronavirus should be taken seriously. I urge you not to wait until your symptoms are so severe, like mine were, that you can barely breathe. If you’re experiencing symptoms, get a test as soon as you can and contact a healthcare worker to see what steps you should be taking to care for yourself. This pandemic is having the worst impact on our communities, and we must make our health a top priority if we are going to survive this pandemic.

Recent anti-immigrant policies have increased the level of fear in undocumented communities about their ability to access necessary healthcare and other safety net programs. If undocumented essential workers such as farm and factory workers disclose COVID-19, this may increase both fear and actual experiences of retaliation and even deportation. To manage these challenges, undocumented individuals often do not get the healthcare they deserve. Undocumented immigrants in detention centers face an even higher risk than the general population. The spread of COVID-19 is inevitable in a system that houses tens of thousands of people in inhumane conditions. As of August 2020, the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency reported that close to 1,000 detainees out of a population of over 21,000 had tested positive for COVID-19.4 They also reported that since testing began in February 2020, 5 people had died after testing positive for COVID-19 while in ICE custody.5

So, why are we experiencing greater impact and loss? While underlying health conditions and other factors that operate at the individual level do contribute to worse health outcomes with the presence of a COVID-19 infection, systemic injustice creates and aggravates these factors.

- The LGBTQ population uses tobacco at rates that are 50% higher than the general population, and it has been well-documented that the tobacco industry has aggressively targeted LGBTQ communities since the mid-1990s.6 Because COVID-19 is a respiratory disease, smokers are especially vulnerable.

- The LGBTQ population also has higher rates of cancer and HIV, both of which can make a person’s immune system more vulnerable to COVID-19. Yet these higher rates of cancer and HIV are catalyzed by injustices ranging from discrimination to taking away people’s rights to comprehensive healthcare to not doing adequate research on the impacts of these injustices on these groups.7, 8

- Indigenous people are three times more likely to be diagnosed with diabetes compared to the general population,9 and this situation is directly connected to historical and present-day traumas and oppression.10 Diabetes is a key characteristic of COVID-19 patients.

- Diabetes, hypertension and asthma are associated with greater risk of death from COVID-19. Black Americans experience all of these illnesses at higher rates than whites,11 both because of racism in the healthcare system and also because of racism throughout our country.12

Further, researchers have found that even if we could wave a wand and statistically correct for these chronic health conditions in individuals, our communities overall are still more likely to experience adverse health outcomes. There’s more to these differences than our individual behaviors in response to unsafe systems. There are foundational and structural reasons that help explain the differences in health outcomes — histories of slavery, colonization and oppression, the robbing of our communities’ wealth, denial of access to healthcare and healthy food, the pollution of our neighborhoods, and forcing us into hazardous living and working conditions. This pandemic has exposed the deep inequities that cause both individual-level health conditions and community-wide trauma and loss from COVID-19. Systemic injustices also create and aggravate systemic-level health factors, like housing, employment, and healthcare and healthcare access, that are killing and harming our communities.

Housing. Healthy homes promote good physical and mental health. During the COVID-19 pandemic, substandard housing, overcrowding issues, and the lack of affordable housing can lead to respiratory infections, psychological distress, and overall poor health.

- Due to housing injustice, Black and Latinx people are more likely to live in areas experiencing outbreaks. Because of rental discrimination, Black people must navigate overcrowding in their communities and are twice as likely as white people to live in smaller-size housing as households with three or more generations, such as grandparents living with children and grandchildren.13 These housing arrangements make social distancing at home highly impractical.

- Indigenous people are often denied access to complete plumbing in their households. With handwashing emphasized as an important measure in preventing the spread of the virus during the pandemic, this imbalance in infrastructure can put Indigenous people at higher risk in the COVID-19 crisis.

- Because of social stigma, isolation, discrimination at home, and other negative social determinants, LGBTQ youth are 120% more likely to be pushed into homelessness than non-LGBTQ youth. Beyond shelter, many rely on food and resources provided by public schools and child welfare agencies. Due to widespread school closures as a result of COVID-19, LGBTQ youth are also at risk of losing access to basic necessities that are provided by schools.

- Many low- and moderate-income immigrant families that can use or qualify for federal housing assistance have been affected by the Trump administration’s implementation of the public charge rule. In Texas out of fear of retribution, some undocumented immigrants, instead of seeking housing assistance, have self-evicted from apartments they could no longer afford.14 With many workers losing their jobs, more and more immigrants are turning to family members and staying in cramped quarters during this pandemic.

Employment. Employment can offer social, psychological and financial returns that can all improve health. Being employed can also provide important benefits like health insurance, paid sick leave, and parental leave. However, Black, Latinx and Immigrant communities have historically been disproportionately pushed into jobs that now increase exposure to the virus and spread it among our families and communities. Many of these jobs, while necessary for our society to function, do not come with adequate, or any, health and family planning benefits.

- Black and Latinx workers are much more likely to hold frontline jobs, such as grocery, convenience, and drug stores, public transit, trucking, postal service, healthcare, child care and social services15 where they can encounter individuals with COVID-19. While these workers may be somewhat more protected from job loss, the work itself exposes them more than other groups to the risk of contracting COVID-19 while doing their jobs.

- Many women of color in particular work in jobs deemed essential, putting this group at higher risk of getting sick as well. Yet, women of color have also often been pushed specifically toward domestic work, work for which they have no job security and that is now mostly not happening due to the pandemic.

- Only 20 states and D.C. have laws that explicitly prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. Only 1 in 5 U.S. companies offered paid family leave for LGBTQ employees.16

- An estimated 6 million undocumented, un-detained immigrants work at the frontlines of the crisis17 as essential employees. Although they are more likely to work in jobs that have experienced a high rate of furloughs or layoffs (housekeepers, nannies), these workers have been left out of any financial assistance from the federal government. Undocumented immigrants are also much less likely to have access to social safety nets as compared to other low-income Americans.

Healthcare and Healthcare Access. Healthcare itself and an ability to access it are clear advantages for positive health outcomes during a pandemic. Yet, for people who need it, healthcare is often denied or out of their reach. In addition to federal guidelines and law, there’s a wide range of discrimination and violence we experience every day that impacts our ability to have adequate healthcare and access to wellness supports and outcomes. Community safety is a very important health determinant for our communities and for how we experience health and wellbeing. The health of our justice and legal systems in this country are also intertwined with personal health.

- An estimated 7.1 million undocumented immigrants are denied health insurance and, as a result, do not have access to primary care healthcare workers (PCPs). For years, they have relied on emergency departments to get medical care. Telling people during a pandemic to avoid hospitals and instead call their primary care healthcare worker leaves those without a primary care doctor with little recourse. This pandemic is laying bare the consequences of limiting access to primary care for people whose status as residents in the country is already under assault by the government.

- In February 2020, the Trump administration expanded who immigration officials judged to be a “public charge,” people deemed permanently dependent on government aid and thus ineligible for a green card. On July 20, 2020, two nationwide injunctions blocked the public charge rule from going into effect during the pandemic. Although seeking healthcare, assistance in housing, food stamps or other safety-net programs remains possible for undocumented immigrants, the fear within undocumented communities is real. The threat of these anti-immigrant policies, along with lots of confusing messages, continues to impact undocumented communities, deterring people from seeking the support and care they need to stop the spread of COVID-19.

- This pandemic is happening against the backdrop of protests against police brutality. Black, Latinx and Native communities are more heavily policed than white neighborhoods. These interactions with law enforcement are often violent and in many cases deadly. According to the research group Mapping Police Violence, Black Americans are 2.5 times more likely to be killed by police compared to a white Americans.18

- Many people of color experience racism through microaggressions, which are brief, subtle insults that can be intentional or not, but lead to elevated levels of depression and trauma for those of us who experience it.19 Racism in all forms also undermines trust in service healthcare workers and caregivers, putting additional stressors on access to healthcare.

- With the novel coronavirus first occurring in China, Chinese American women and other Asian Americans are dealing with concerning reports of rising xenophobia and with racist anti-Asian threats and attacks surfacing across the country and putting their mental and physical health at increased risk.

- Collective, intergenerational traumas, like slavery, mass incarceration, colonialism, and deportations, are drivers of women of color being more likely to experience unsafe conditions due to domestic violence. Although domestic violence impacts women from all ethnicities, there may be additional challenges for women of color, especially immigrant and undocumented women, who may face limited resources, language barriers, and fear of deportation, in gaining physical and mental safety.

- There’s also scientific research that shows how racism and xenophobia create daily stressors that over time have horrible impacts on our bodies at a cellular level. Arline Geronimus proposed the “weathering hypothesis,” which illustrates how racism builds up in our system over time and eventually impacts our organs and overall health.20

- Undocumented immigrants are more likely to be made sick and die navigating a society and social systems that are unsafe and deadly for them.21 Anti-immigration policies and laws that undocumented immigrants, along with the stressors they experienced in their home countries, as well as in their journey to this country, affect the health outcomes of their communities. Undocumented immigrants often come from countries with long-term war or civil unrest. On top of that, they often experience many forms of trauma during their migration, including imprisonment, rape, ethnic cleansing, physical violence, and torture.

- LGBTQ people have to fight every day for their families to be recognized under the law. Same-sex couples raising between 2 and 3.7 million children live in states that do not explicitly protect them from discrimination, which increases risk for poverty and creates more housing insecurity, in turn making health disparities and social isolation even worse.

What We Need to Know

Fact

Fiction

Fact

Most people who get COVID-19 have mild or moderate symptoms and can recover from it, if they have supportive care. However, certain pre-existing conditions can aggravate this disease. TRUE

COVID-19 is an illness that can affect multiple organs, including the lungs and kidneys. COVID-19 is much more severe than the seasonal flu. TRUE

Fiction

Symptoms, Treatment, Care and Prevention

People with COVID-19 have reported a wide range of symptoms, ranging from mild symptoms to severe illness. Some people do not have any symptoms. Symptoms may appear two to fourteen days after exposure to the virus. People with the following symptoms may have COVID-19.

- Fever or chills

- Cough

- Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing

- Fatigue

- Muscle or body aches

- Headache

- New or recent loss of taste or smell

- Sore throat

- Congestion or runny nose

- Nausea or vomiting

- Diarrhea

This list does not include all possible symptoms. Most people with COVID-19 have mild to moderate symptoms and recover on their own. Less commonly, COVID-19 can lead to pneumonia, other severe complications, hospitalization or death.

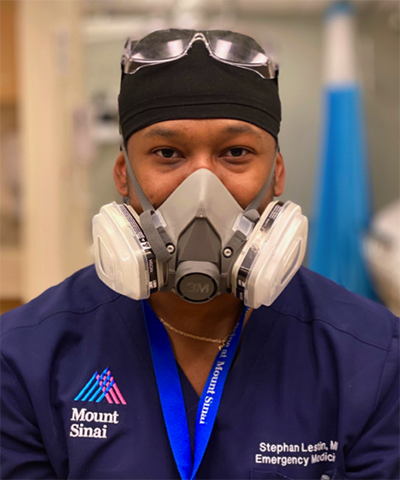

A Defining Moment for Two Young Physicians

Dr. Stephan Lestin (left) was training in Manhattan when COVID-19 hit New York City (NYC) and Dr. Dara Khatib (right) was in Brooklyn. They were both finishing their first year of Emergency Medicine residency. COVID-19 infection rates have improved in NYC but this pandemic has changed us as physicians. It was a harrowing experience. We spent days and nights trying to save those who were seriously ill with this virus. Every shift was filled with the constant alarming bells of monitors that signified low oxygen and the constant sirens of ambulances that brought in more incredibly sick patients — both young and old. Meanwhile, we could only think about all of the patients we would see affected by this disease — all the phone calls we would make and all of the video calls we would do with concerned relatives to tell them the status of their loved ones.

We want everybody to know that one of the most effective means to prevent disease transmission is wearing a mask that covers both your nose and mouth.

We are still trying to learn about how this disease works in the body, but we want everybody to know that one of the most effective means to prevent disease transmission is wearing a mask that covers both your nose and mouth. Also, a negative test does not necessarily mean you do not have the virus. Unfortunately, COVID-19 tests are not 100% accurate at this time. It is entirely possible to be without symptoms and have a negative test, but still be infected. If you have known exposure to COVID-19 and have a negative test, you should still self-isolate for 2 weeks from your last known exposure to ensure that you do not pass the virus on to others.

We must educate ourselves and understand our symptoms and the risk COVID-19 presents in our communities.

Known Increased Risk of SEVERE Illness from COVID-19

- Obesity (body mass index >30)*

- Type 2 diabetes mellitus*

- Heart conditions,*, such as coronary artery disease (past heart attack), heart failure, or cardiomyopathy

- Chronic kidney disease (CKD)

- Sickle cell disease *

- Cancer*

- Having been recently treated for cancer*

- Immunocompromised state from an organ transplant

* Indicates that Black people, Indigenous people and people of color may be more likely than white people to have these conditions. These conditions are often referred to in the news and by healthcare workers as comorbidities.

Possible Increased Risk of Severe Illness from COVID-19

- High blood pressure (hypertension)

- Smoking

- Asthma (moderate to severe)

- Pregnancy

- Cerebrovascular disease (disease of the blood vessels of the brain), such as stroke

- Neurologic conditions, such as dementia

- Thalassemia

- Cystic fibrosis

- Immunocompromised state, including HIV, use of steroids, immune deficiencies, recent bone marrow transplant or blood products transfusion, use of corticosteroids

- Liver disease

- Pulmonary fibrosis

- Type 1 diabetes mellitus

- Children with neurologic, metabolic or genetic conditions also have increased risk of severe infection

Fact

We’re still learning about how the virus spreads, but we know much more today than we did at the start of the pandemic. TRUE

Here’s what we’ve learned: The virus (SARS-CoV-2) that causes COVID-19 is thought to spread mainly from person to person, and mainly through respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks. These droplets can land in the mouths, noses or eyes of people who are nearby or possibly be inhaled into the lungs. Spread is more likely when people are in close contact with one another (within about 6 feet). We’re starting to see that spread can also happen when people are in a building with a shared air space. The virus can circulate through HVAC systems or the air, infecting people farther than 6 feet apart, even in other rooms or floors. This means that spread can happen even when people are physical distancing. COVID-19 also seems to be following community spread, which is when someone picks up the illness by coming into direct contact with an infected person.*

*This statement reflects the consensus of the medical and public health community as of 9/28/2020.

Fiction

Coronavirus spreads through:

- Houseflies* FALSE

- Mosquito bites* FALSE

- 5G mobile networks* FALSE

(from WHO website 7/7/2020)

*These statements reflect the consensus of the medical and public health community as of 9/28/2020.

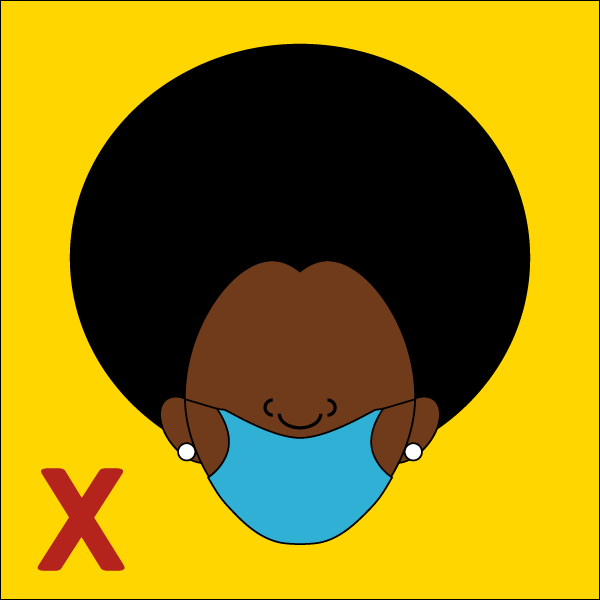

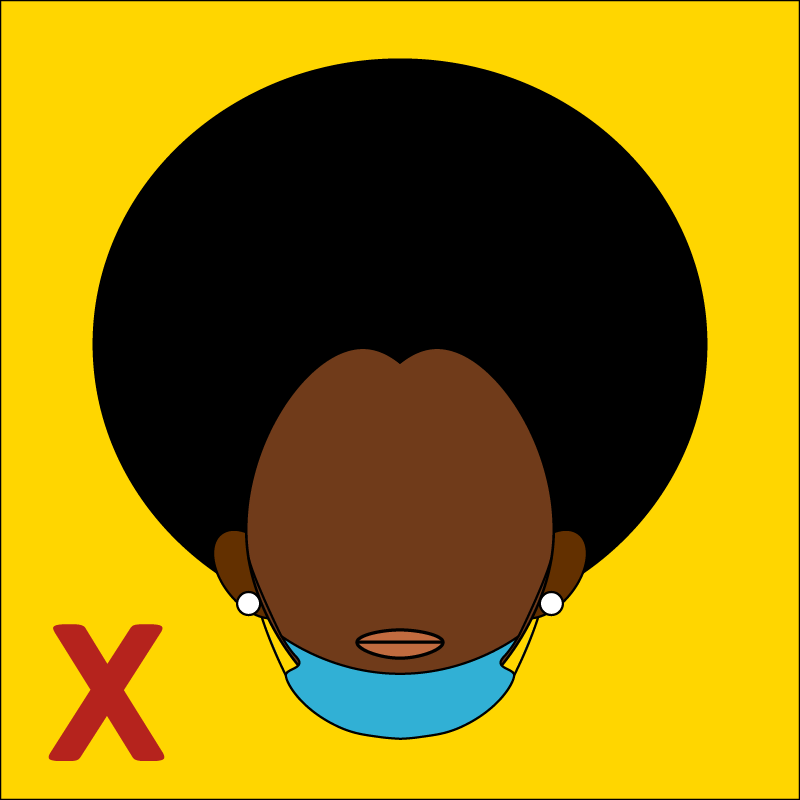

- Wear a mask in public and when around others outside your home. The mask should cover both your nose and mouth. If it doesn’t cover both, your mask isn’t providing protection to you or protecting others.

- Open windows and doors and encourage fresh air ventilation. Ventilation and airflow are extremely important. Bringing in and circulating fresh or outdoor air helps to decrease exposure to the COVID-19 virus and prevents the virus from lingering in the air and being spread. (Refer to the Ventilation section for specific hacks you can do at work or home to increase air flow.)

- Maintain social distance by increasing the space between individuals and by decreasing the frequency of contact. Keeping physically distanced reduces the risk of spreading the virus. (Ideally maintain at least 6 feet between all individuals, even those who are asymptomatic.)

- Shelter in place, except for essential activities.

- Wash your hands frequently for at least 20 seconds.

- Avoid touching your eyes, nose and mouth.

- If you’re experiencing symptoms, don’t go out.

Fact

There is currently no licensed medication to cure COVID-19. There is no vaccine for COVID-19. TRUE

Until there is a medication or vaccine, your best protection against COVID-19 is to practice public health recommendations like wearing a mask, washing your hands, maintaining social distance, opening windows to increase air flow, and sheltering in place as much as you can. TRUE

Fiction

Spraying or introducing bleach or other disinfectants into your body will protect you against COVID-19. FALSE

According to the WHO website this practice can be dangerous. Neither hydroxychloroquine nor any other drug can cure or prevent COVID-19. TRUE

How and Where to Get Tested

- If you feel ill and need a test, you can choose which of the following options to call for help getting a test.

- Your healthcare worker

- Your local health department

- Your local pharmacy

- Call ahead to ensure the healthcare worker or healthcare center has COVID-19 testing available.

- If you feel ill and are experiencing severe shortness of breath or confusion, call 911. It’s especially important to seek immediate care if you are having trouble breathing. Don’t wait until you are severely ill to reach out. A healthcare worker can help you determine what steps you should take if you are ill.

- If you get a COVID-19 test, you should self-quarantine as much as possible while awaiting the results. Waiting periods for results can be up to two weeks. Without self-quarantine during that time, you may be exposing others to the virus if you have it.

- If you get a negative result on your test, you can continue to physically distance and monitor symptoms. If symptoms increase, talk to your healthcare worker to help you understand the test result and to explore the best next steps for you to take for your health.

- If you get a positive result on your test, you should self-quarantine as much as possible. Work with family and friends ahead of time to make a shared plan for how to help the infected person to receive care, self-quarantine, go to the hospital if symptoms are severe, and reintegrate after quarantine.

Types of COVID-19 Tests

Viral Test (Diagnostic Test)

The viral test is the test to take if you think you have an active COVID-19 infection.

- The viral test includes two tests.

- The molecular test detects the virus.

- According to Harvard Health Publishing, the reported rate of false negatives is as low as 2% and as high as 37%. The reported rate of false positives — that is, a test that says you have the virus when you actually do not — is 5% or lower.

- The antigen test detects the viral genetic material (specific viral proteins).

- According to Harvard Health Publishing, the reported rate of false negative results is as high as 50%, which is why antigen tests are not favored by the FDA as a single test for active infection.

- The molecular test detects the virus.

- The sample is collected by nasal (most common) or throat swab or in saliva.

- The viral test DOES NOT show if you have had COVID-19 in the past. Only active infections can be properly diagnosed with this type of test.

- Frequently, this form of testing is referred to as the Rapid or POC (Point of Care) Test.

- It is important to note that these tests are operator-dependent, meaning that although this is the most accurate form of detection, if the operator (person administering the test) does not get a sufficient swab sample, or the sample does not have a lot of virus in it, it can affect the results. The nasal swab test is uncomfortable; however, remaining still during the test will help the operator.

- Results from a viral test can be read as follows.

- Positive test result: You have an active COVID-19 infection.

- Negative test result: COVID-19 was not detected in the sample provided (as noted above, this does not mean it can be said with 100% certainty that you do not have COVID-19). Therefore, no matter your test result, if you do not feel well, take preventive social distancing measures.

Antibody Test

The antibody test could tell you if you have been infected by COVID-19 in the past. It does not diagnose an active infection.

- The sample is collected by blood draw or fingerstick.

- It is important to note that the antibody test looks at the body’s immune response to the COVID-19 infection. Therefore, it can take days or even weeks before a person who had COVID-19 would test positive for this test.

- Results from an antibody test can be read as follows.

- Positive test result: Even if you did not have symptoms in the past, a positive result means you had COVID-19 in the past.

- Negative test result: You have not had exposure to COVID-19. Current evidence suggests that antibodies fade after 2 to 3 months, so this test is not a perfect diagnostic of prior infection.

- Currently, we do not know if antibodies for COVID-19 protect against reinfection, and therefore even with a positive antibody test result, it is important to continue social distancing measures.

- The antibody test should not be used to determine if you can go back to work. If you were sick, do not return to work until you are 2 weeks without symptoms. (There are conflicting views on how long to wait to return to work, from 10 days to three weeks depending on severity of the illness.)

- The antibody test is being used to help the medical community understand more about COVID-19 because this disease is so new. If you are unsure of which test to get, call your primary healthcare worker or an advice healthcare worker at your local health department.

- According to Harvard Health Publishing:

- “What about accuracy? Having an antibody test too early can lead to false negative results. That’s because it takes a week or two after infection for your immune system to produce antibodies. The reported rate of false negatives is 20%. However, the range of false negatives is from 0% to 30% depending on the study and when in the course of infection the test is performed. Research suggests antibody levels may wane over just a few months. And while a positive antibody test proves you’ve been exposed to the virus, it’s not yet known whether such results indicate a lack of contagiousness or long-lasting, protective immunity.”

If you are diagnosed with COVID-19 or get a positive viral (not antibody) test result, shelter in place as much as possible. Do not go to school or to work, even if you are an essential worker, unless exempt from quarantine (as some workers such as healthcare workers are). Only leave your shelter to get essential medical care or to get basic needs such as groceries, if you have no other way to get them.

To protect others in your household from getting sick, you can take the following precautions:

- Stay at least 6 feet from everyone in your household. If you have one, use your outdoor space, or try to spread out in the house as much as possible. Distance is the best way to protect others. If you cannot maintain this distance from others, wear a face covering that covers your mouth and your nose.

- Use a separate bathroom if available. If you share a bathroom, close toilet covers before flushing, and disinfect surfaces and fixtures after each use.

- Wash your hands often with soap and water for at least 20 seconds.

- Cover your mouth and nose with a tissue or your sleeve when sneezing or coughing. Do not use your hands to cover your sneeze or cough. Immediately throw out tissues and wash your hands afterward.

- Clean surfaces that are frequently touched, such as counters, doorknobs and phones. Clean them after each use or at least once every day. Use a household cleaning spray or wipe.

- If you share a bed with someone, sleep head-to-toe or have one person sleep on the couch or floor.

- If you need to be in the same room as others, move furniture around so that you can sit farther apart.

- Do not share personal household items, such as glasses, cups, eating utensils and towels.

- Do not have visitors come to your household.

- Open windows to improve airflow.

Most people do not require testing to decide when they can be around others; however, if a healthcare worker recommends testing, they will let you know when you can resume being around others based on your test results. The following guidelines may be helpful as well.23

If you think or know you had COVID-19, you can be around others after:

- 10 days since symptoms first appeared, and

- 24 hours with no fever without the use of fever-reducing medications, and

- Other symptoms of COVID-19 are improving. **Note: Loss of taste and smell may persist for weeks or months after recovery and these symptoms alone need not delay the end of isolation.

If you tested positive for COVID-19 but had no symptoms, you can be around others after:

- 10 days have passed since you had a positive viral (not antibody) test for COVID-19.

If you had a severe illness or are immunocompromised, consider the following:

- People who are severely ill with COVID-19 might need to stay home longer than 10 days and up to 20 days after symptoms first appeared. People who are severely immunocompromised may require testing to determine when they can be around others. Talk to your healthcare worker for more information. If testing is available in your community, it may be recommended by your healthcare worker. Your healthcare worker will let you know if you can resume being around other people based on the results of your testing.

- Your doctor may work with an infectious disease expert or your local health department to determine whether testing will be necessary before you can be around others.

What We Can Do

Much of what we need to keep our communities safe in this pandemic relies on us holding decision-makers at every level accountable. We need paid leave, healthcare access, childcare, safe working conditions and a host of other supports and resources. We must continue to win these essential services through the power of our activism in our healthcare settings, workplaces and communities, and with the power of our vote.

Understanding Your Visit

Seeking healthcare can be overwhelming: new information, new treatment plans, tests, upcoming appointments. To ensure you get the most out of your visit, ask the healthcare worker at the end of each visit to summarize and explain the visit. It may be helpful to keep these questions in mind.

- What are the changes being made to my treatment plan?

- What are upcoming tests or referrals I need completed before my next appointment?

- (If there are new medications being added, make sure to ask:) How should I take the medication prescribed and what are the common side effects?

If you can repeat back the summary of the changes made and the plan, you fully understand the next steps for your treatment plan. If you cannot summarize it, ask more questions until you have a full understanding.

Know Your Rights

- If you do not feel comfortable with your nurse or doctor, you have every right to ask to see a different healthcare worker for your next appointment. You do not have to provide a reason.

- You have a right to ask for a translator in your language. If the healthcare worker states that they can speak in your language, you can still request a translator if you feel they are not fluent or you are not understanding the information provided. You can always request a translator.

- “Doctor, I appreciate your effort to communicate with me, but I am still having difficulty understanding. I would like to use a translator so I can make sure I understand.”

- You have a right to be informed on your health status. If you do not understand any of the information given by the healthcare worker, you have every right to ask the practitioner to explain the information. You can ask about results, procedures, consents, diagnosis and treatment plan. All of these components are necessary as a part of your healthcare.

- You can request and expect the provider to discuss all risks associated with any procedure. Any questions regarding the risk should be answered frankly and clearly by your provider, and you request clarity if the risks are not clear to you.

- Before signing, any questions in terms of the need for the procedure and the risks involved should be fully answered by the healthcare worker. You can also ask what refusing consent means for your care, a question that is an important part of your self-advocacy. All consent forms should include the following information.

- Name of patient with appropriate patient markers (such as medical record number or date of birth)

- Name of procedure

- Location site on body

- List of risks and benefits of receiving the procedure

- If you have asked for a diagnostic test or procedure and have been refused by your physician, you can request the doctor document this in your chart.

- You have the right to know who’s in the room. Whether going to the doctor’s office or to the hospital, there are a lot of people involved in your care. Sometimes this can be unsettling and also exhausting, as you will have to repeat your story multiple times for different healthcare workers. You have the right to know the identity of anyone involved in your care, whether they be physicians, nurses, or students.

- For more help navigating the healthcare system, check whether there is an official individual or department whose job it is to help patients. Often this is referred to as a hospital ombudsman or patient advocacy department.

Communicating with Your Doctor

The relationship between patient and doctor is important and has been shown to positively impact health outcomes. Patients who feel more comfortable with the physicians and healthcare workers they encounter are able to share all pertinent information that helps these practitioners make more informed decisions about immediate patient care and long-term wellbeing.

Discuss Your Work and Home Life

Many healthcare workers know that their patients have to sacrifice a lot to see them (whether it is taking a day off of work, finding reliable and safe transportation, balancing child care, or financial stressors). Share any struggles you are having, including time commitments for scheduling tests and appointments or financial roadblocks to care so the healthcare worker has a better understanding of these struggles and how they can affect you getting tests, procedures, and treatment on time. Emphasizing these issues to your healthcare workers allows you to work as a team for your health success.

What to Say to a Healthcare Worker to Help You Get Better Care

- Procedures and Diagnostic Tests

- “Could you please explain the procedure to me? What are the steps?”

- “What can I expect on the day of the procedure or test? How can I prepare?”

- “What is the purpose of this procedure? Why do I need this procedure?”

- “What are the risks involved in this procedure? Am I at high or moderate risk for any complications mentioned?”

- “What are the possible short-term and long-term side effects of the treatment or procedure?”

- “What are the possible outcomes if I do nothing?”

- If you have asked for a diagnostic test or procedure and the healthcare worker has refused your request, you can ask the healthcare worker to document this refusal in your chart.

- “Although you are not recommending this test or procedure, please document in the chart that I requested this test and the reason why I am not a candidate for it.”

- Knowing Who Is in the Room

- “Hello, I am happy to answer your questions, but before I do, could you please introduce yourself and your role in my care?”

Filing Complaints If You Have Experienced Discrimination in the Healthcare System

There are no universal antidotes to the discrimination you may encounter when seeking care, but below are some places you can reach out to file a complaint or make a record of your experience. By filing a complaint you have documentation if you decide to pursue legal avenues, and your complaint may lead to a future patient being treated better.

- File a complaint to the hospital or clinic system detailing your experience.

- Also, file a complaint with your health insurance.

- Many hospitals have patient experience coordinators. File a complaint with that person as well.

Essential workers have continued reporting to their physical places of employment during the pandemic. Black and Indigenous workers and people of color, including immigrants in tenuous job situations, make up a big portion of essential workers who are at increased risk of getting COVID-19, including factory workers, agricultural workers, cooks, cashiers, delivery workers and transit workers, and those providing care in hospitals and nursing homes. COVID-19 has cost the lives of people who have had to continue to work throughout the pandemic—often with low pay and limited benefits—while also putting their families and communities at greater risk. Pre-existing racial health disparities only exacerbate the situation. In this section, we provide information that can help you advocate for and create a safer workplace.

I work for the second largest poultry-producing company in the world, Tyson Foods and I do not feel safe.

Since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, many of my coworkers have tested positive for COVID-19. Throughout this entire ordeal, I’ve been disappointed in Tyson, as nothing has been done to ensure the safety and health of any of us in the factory. Once a person tests positive, they are sent home for five to seven days. If they no longer have visible symptoms, they are allowed to return to work.

Even though I haven’t tested positive, I am fearful. Tyson has not implemented any real policies to protect those of us who have in fact come in contact with those in the factory who tested positive. Right now, the only new provision that have been made is the distribution of one mask per person, per shift. This is unacceptable, as working conditions are not the best. In the factory, we work very close to other people.

In addition to the poor working conditions, there is a lot of discrimination and racism within the company. We are suffering from poor working conditions.

Since the pandemic started, we are missing lots of workers. Those who are working, are working two or three times as hard to make up for the absent workers because Tyson expects us to deliver as though we have the normal amount of workers.

On top of the poor working conditions, Tyson is robbing us of our time. We only get one break to eat. It is 20 minutes only, and it starts the moment you leave the line, which includes the time it takes to take off the PPE and heat up the food. This is only 20 minutes to do all of that and return to the line. If I do the math, we are only getting about 12 minutes to sit and actually get a break. We are allotted one bathroom break per shift, and it must not be longer than 10 minutes.

Even though my coworkers and I have tried to unite to demand action from Tyson, we have been denied. In the beginning of the summer, the president of the union made a petition to Tyson to increase the safety and protection of workers and increase the wages during the pandemic (Hazard pay).

We successfully gathered 300 signatures and submitted the petition to corporate. Unfortunately, Tyson rejected the petition and denied all of our demands. Our union is fairly new. Right now, we don’t have a lot of members. The union organizer has done a lot to protect the workers so that Tyson will do better by its workers. She’s even organized protests, but when she brought the petition to Tyson the police kicked her out.

It’s clear that Tyson does not care about me or the safety of any of its employees. We are not important to them. So, it’s up to me to try to protect my family.

When I’m at work, I sit alone at a table. I try to touch as little as possible, and I limit my interactions with everyone. I only take my mask off to eat. When I arrive at my house I leave my clothes in the garage.

All of this is infuriating, as I work hard for a company that does not value me.

To all the Black and Brown people who find themselves in similar working conditions, I say don’t be scared to strike. If we all strike, they will notice because they need us to work.

Essential Workers and Ventilation Español

This section on ventilation is a part of the #ClearTheAir campaign from Last Mile, a Forward Together partner on COVID-19. For more information on ventilation and safety, go to the website www.CovidStraightTalk.org for a workers’ toolkit that has additional tips and resources on air ventilation and COVID-19.

Exposure to the virus is a workplace hazard. The coronavirus can stay in the air for a long time and may pass through vents and HVAC systems. This coronavirus can float into your nose or mouth, even if you’re far away or in another room from someone who is sick. The quality and maintenance of HVAC systems are critical to reducing the spread of harmful particles indoors.

Employers should provide clear, reliable, and accessible safety information and put in place protocols to protect their workers. While such precautions are an employer’s responsibility, it is important for you to find out what measures your employer is taking to protect their employees from getting and spreading the virus.

To reduce the risk of spreading the virus, employees should not be at work if they have COVID-19 symptoms. In the face of this pandemic, staying home while sick protects others.

If you are in doubt, try your best to keep your mask on at all times at work and wash your hands frequently. This is your first line of defense against catching or spreading the virus. Wearing a mask is like giving a hug; it’s showing great care and respect for your coworkers.

And remember, when in doubt, get MAD! Mask, Air, and Distance.

Mask!

Wear a mask! By wearing a mask, you will protect yourself and others from getting and spreading COVID-19. We show care and respect for our team and our loved ones when we wear a mask. Masks are our first line of defense against the virus.

DO

- Wear a mask whenever you are in public, especially in crowded places

- Wear your mask at all times while at work, even if no one else is around

- Avoid touching your face or mask with your hands

- Sneeze or cough into your shoulder or elbow even when you are wearing a mask

- Encourage the people around you to wear a mask. Show appreciation to others for wearing a mask

- Consider wearing goggles, gloves, or a face shield as extra protection

- Wash your hands often. If soap and running water are not available, use a hand sanitizer containing at least 60% alcohol

DO NOT

- Go out in public without wearing a mask

- Take your mask off at work, even if you are alone

- Leave your nose or mouth exposed with a mask that doesn’t fit well

- Dangle your mask from your ears, wear it under your chin, or rest it on your forehead

- Remove your mask to talk (people can hear you through your mask)

- Share equipment or tools (phones, utensils, sunglasses)

What to Ask Your Employer

- Employees should be provided with fresh disposable masks or reusable cloth masks, as well as fresh gloves. Wearing masks indoors and in public spaces should be mandatory for all.

Air!

Keep indoor air fresh. Open windows to get outdoor air flowing through the space. The virus can stay in the air for a long time, may pass through vents and HVAC systems, and can float into your nose or mouth, even if you’re far away from others or alone in a breakroom.

DO

- Ask about ventilation in your workplace (see below for questions to ask your employer)

- Work outside when possible (this allows physical distancing and maintains the greatest amount of fresh air around you)

- Open windows and doors to improve air flow, when possible*

- Turn on fans to get more outside air (freely moving air decreases the risk of breathing in virus particles through your nose or mouth)

- Use a humidifier to maintain a humidity level between 40% to 60% (Indoor humidity24 higher than 80% can lead to mold and other types of harmful pathogens. Viral particles float in the air longer in spaces with very low humidity. Prolonged exposure in these spaces can dry out your nose and weaken your immune system.)

DO NOT

- Work directly under HVAC vents

- Stay in a confined space without good air circulation

What to Ask Your Employer

- MERV 13+ and HEPA filters are considered the best options for filtering virus particles from the air. Are these filters being used? Can they be upgraded?

- Is the HVAC set to high refresh? “High refresh” or “economy” mode brings more outdoor air in, helping to keep the inside air clean.

“Can we open windows?*”

- Opening windows increases the amount of fresh air in the room and breaks up virus-carrying clouds in the air.

“Is the recommended maintenance schedule for the HVAC system being followed?”

- Every HVAC system has different maintenance guidelines, and should be followed properly. Ask your employer if regularly scheduled maintenance and cleaning is being done.

“What protocols are in place to ensure that employees are not at risk of compromised airflow when HVAC maintenance is being performed?”

- HVAC maintenance can disrupt airflow, so it’s best if it can be done after hours or when workers are not present.

*This is context dependent. If you’re in a job environment that has lower air quality (such as one with hazardous fumes or smoke), you may not be able to open a window.

Distance!

Keep your distance! Stay at least 6 feet apart (2 meters) from others. You are at a higher risk of getting COVID-19 if you work indoors or live in a multi-occupant home or building.

DO

- Take your temperature before work, and stay home if you have a fever or other symptoms of COVID-19

- Wear your mask at all times while at work and in public places

DO NOT

- Congregate in breakrooms or other crowded places inside or outside

- Feel ashamed if you get sick — COVID-19 can infect anyone

What to Ask Your Employer

- Working from home is the safest option if you are able to do so, because it’s easier to limit your exposure to others and to the virus.

“How can the amount of time workers are in close proximity to each other be reduced?”

- Suggest that your employer space out workstations, stagger shifts, or arrange flexible working hours to limit the number of people in the workplace at one time.

- Reducing the number of people and the amount of time they spend inside will lower the risk of infection.

All over the country, essential workers are coming together and organizing to demand safe working conditions and fair pay. These workers are keeping us safe in quarantine, but many of them are raising concerns that they do not have the protections they need to do their jobs safely.

Many of them have organized collective actions that have led to some important gains. For example, since walking off the job because of concerns over lack of social distancing policies in processing plants, workers at Perdue Farms are now receiving four weeks of paid leave for anyone who gets sick with COVID-19. Detroit bus drivers got their government to boost sanitation measures for public transit workers after a brief strike.

If you feel your employer is putting you and your colleagues in a dangerous situation, talk to your colleagues and see if they feel the same way about working conditions. Making change is much more powerful when colleagues stand together. These additional considerations may be helpful to planning and taking action.

- Do not use work time to talk about the issue

- Make sure you are calling for positive change that will improve working conditions for all employees

- Make sure statements about your employer are related to how you and your coworkers are treated at work

- Do not use your work computer or work email

- Make sure all of the statements made about your employer are true

You and your colleagues may want to take one or more of the following actions.

- Express grievances via social media

- Start a petition and collectively deliver it to your employer

- Picket outside of your workplace and invite local news to cover it

- Write letters to an elected official

- Form a union!

Unions remain perhaps the most powerful means of ensuring that safety protections are actually enforced.

Steps to Forming a Union

- Build an organizing committee

- Come up with union demands

- Get majority support: Usually worker signs a card or petition indicating they support establishing a union.

- Vote in the union: After you have shown majority support for the union, you will hold an election where each worker votes to form the union. You need a simple majority (50% of voting workers plus 1) to form the union.

- Negotiate a contract: once you have established a union, you will form a bargaining committee and sit down with your employer and negotiate a contract with solutions that address the workers’ concerns about the workplace.

Established unions have organizers who can help workers in non-unionized workplaces form a union. Reach out to local union offices in your industry for support in forming a union.

More resources for workers:

- #ClearTheAir (http://cleartheair4.us) is providing toolkits for workers and employers on how to reduce the risk of getting and spreading COVID-19 through the air at work or home. Toolkits are also available in Spanish.

- Learn more about the process of forming a union

- Studio Rev’s Volador (www.StudioRev.org/volador) is an illustrated Know Your Rights Toolkit for workers, including undocumented workers, and is also available in Spanish.

- The National Employment Law Project (www.nelp.org/publication) offers multiple guides.

- Health and Safety Rights for workers.

- A review of which states have adopted comprehensive COVID-19 protection for workers

- Resources for unemployed frontline workers

- Immigrant worker rights FAQ, also available in Spanish here

- The National Immigrant Law Center (www.nilc.org) offers a set of resources (webinars, blog posts) to understand immigrant worker rights and COVID-19.

Fighting for your right to live shouldn’t put you and your loved ones at greater risk. It is not just the justice system but also the healthcare system that has failed us, and Black people specifically. Over 1000+ epidemiologists, public health officials and healthcare workers signed a letter to support protesting against white supremacy and police brutality during the COVID-19 pandemic. While it is deeply unjust that we must risk our lives in a pandemic to protest another threat to our lives, we hope this guidance helps you do so as safely as possible.25

BRING*

- A mask! (It may be difficult to stay 6 feet apart; however, wearing a mask protects you and anyone you come in contact with at the protest. A face mask also helps protect your identity in any photos or videos that may be taken at the protest.)

- Water and portable snacks

- ID and cash (enough for travel, food, and to make a phone call if necessary)

- Goggles (as an option to protect eyes from irritants like tear gas)

- Earplugs (as an option to protect ears from loud noise)

- Hand sanitizer

- A change of clothes (in case chemical irritants are used)

- A first aid kit

- Signs and noise makers (singing and shouting chants causes aerosols to be released into the air and spread the virus, which is minimized by masks, but there is still risk)

- A backpack or bag that can carry all of your necessary items (remove anything that is nonessential)

*There are varying opinions on bringing phones to protests; do so at your own discretion.

DO

- Wear comfortable shoes

- Wear comfortable clothing that covers arms and legs (difficult in the summer but use of lightweight, long-sleeved clothing/pants is still recommended, as this serves as a barrier for protection from irritants, plus sun safety)

- Write out an emergency contact number somewhere outside of your phone (some people write this number on their arm in case they do not have access to their items)

DO NOT GO OUT PROTESTING IF:

- You feel unwell

- You have been exposed to someone with COVID-19:

- You do not need to self-isolate after a protest UNLESS you are feeling symptomatic. However, a mask should be worn.

- If you feel symptomatic, self-isolate (do not go into work/school, do not attend another protest), and get tested for COVID-19.

- If you’ve been exposed to COVID-19, get tested. Get a test 5 days after exposure and avoid contact with anyone immunocompromised or those who are age 65 and older while waiting to get tested and while waiting for test results.

Just like protesting, casting your ballot can be done safely and effectively. But it is critical to plan.

First, make sure you’re registered to vote!

Some states allow online registration. Other states require you to print and mail in a form. These resources may help you to make sure you’re registered to vote by your state’s deadline.

- Voter registration deadlines

- Know the vote-by-mail rules in your state.

Voting Early

- Most states offer early voting. Early voting lets registered voters cast their vote on specified dates before Election Day.

- If your state has early voting, everyone in your state can vote early.

- Check to see when early voting starts and ends in your state at www.vote.org/early-voting-calendar/.

Voting in Person on Election Day

- Expect to see long lines, as we have seen from primaries in various states, and be prepared for a wait. Bring a bag with snacks and water (enough for a few hours).

- Check to see if your state offers early voting; if you vote early, you may be able to avoid long lines and come into contact with fewer people.

- Wear a face mask at all times of the polling process (while waiting in line, in the voting booth, and when exiting).

- Bring hand sanitizer with you. Hand sanitizer should be offered at the polling site, but it is not guaranteed.

- Avoid touching your face.

- Avoid physical contact with anyone in line, even if you see people you know. Maintain at least 6 feet distance from others.

- Bring your own pen, so you will not have to use one from the polling site that may have been used by others.

Voting by Mail

If you can still request a mail-in-ballot from your state, do so. It is unclear what the state of the COVID-19 pandemic will be in your area in November. For that reason, we encourage registering for mail-in ballots, as people can safely voice their vote remotely. Also, if someone is positive for COVID-19 or has been in close contact with someone with COVID-19 (at home), they should not go out to vote. Mail-in ballots help ensure voting can still happen.

If you’re voting by mail and are concerned about delays, you may want to try the following actions:

- Err on the side of caution and vote as early as possible!

- Make sure to fill out the entire ballot, sign it and seal the envelope.

- Once the ballot is ready to mail in, check to see if there’s a ballot drop box in your area.

- If your state does not allow drop boxes, look up your local registrar or elections board and drop it off there.

- Check to make sure your ballot has been counted.

- Help everyone in your network do the same!

COVID-19 is having a complex range of challenging impacts on the economy, work life, neighborhood and family programs, schooling and political leadership, impacts that are leaving our communities even more negatively affected by housing injustice. During the pandemic, our communities, and particularly single mothers, people of color, people with disabilities and formerly incarcerated people, are most at risk of being evicted. With housing being an important aspect of physical and mental health and wellbeing, eviction contributes to the systemic health and wellbeing injustices that our communities already face.

The consequences of eviction are also unique during a pandemic. Because people need to quarantine if they become sick with COVID-19, staying housed is important for the people who are sick, but it’s also important to help stop the spread of COVID-19 to wider groups and populations, and especially for stopping the virus from hitting our communities even harder. Because people need to quarantine if they become sick with COVID-19, staying housed is important for people who are sick, but it’s also important to help stop Covid’s spread to wider groups and populations, and especially for preventing the virus from hitting our communities even harder.

If threatened with eviction, there are steps you can take to advocate for yourself and your communities.

- Don’t leave your home right away. You can first defend yourself in court.

- Know your rights and learn about actions you can take to defend yourself.

- Get help from people and sources that can fight the eviction with you. Your city likely has legal aid, tenant rights and housing justice organizations that can support you.

- Prepare so that when you get to court you are ready to make your case. Gather important documentation, such as a copy of your lease agreement and evidence of prior rent payments you’ve made.

You can also consult the following resources for support.

- NationalEviction.com’s directory for state-specific eviction processes: https://nationalevictions.com/home/welcome/states-eviction-process/

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s directory of state-specific tenants rights: https://www.hud.gov/topics/rental_assistance/tenantrights

- The National Housing Law Project’s initiatives: https://www.nhlp.org/initiatives/

- The National Housing Law Project’s resources page: https://www.nhlp.org/campaign/protecting-renter-and-homeowner-rights-during-our-national-health-crisis-2/

- Legal Services Corporation’s directory for legal aid: https://www.lsc.gov/what-legal-aid/find-legal-aid

- Support from Fannie Me: https://www.knowyouroptions.com/rentersresourcefinder

- Support from Freddie Mac: https://myhome.freddiemac.com/renting/lookup.html

- Eviction Lab’s COVID-19 eviction state-specific protection expirations: https://evictionlab.org/covid-policy-scorecard/

Community Care

- Patient. On admission to the hospital, confirm or designate your healthcare proxy. This is an individual who legally can make decisions for you in the event you are unable to do so. If they are not aware, inform this person on admission to the hospital that they are your proxy.

- If the patient has a living will, bring a copy to the hospital.

- Let your proxy know if you have strong wishes about measures such as chest compressions or intubation. These are difficult conversations but are necessary. Making these decisions removes the stress and guilt felt by family members who are unclear of their loved ones’ wishes.

- Caregiver. If they are comfortable sharing their information, ask your loved one (the patient) to call you while the medical team is visiting your loved one, as it is the best opportunity to be updated on the plan and your progress. Choose one person to be the point of contact.

- Have a pen and paper handy to take notes and write answers to any questions.

- Prompt your loved one to ask any questions they may have.

- Translate and explain anything your loved one does not understand.

- Ask the healthcare worker clarifying questions if you don’t understand something they’ve said.

- If your loved one is admitted to the hospital, know the following information to keep updated on your family member.

- Patient’s room # and bedside phone #

- Hospital team

- Location in hospital (ward: ICU, medical floor, step-down, etc.)

- The best way to stay connected with your loved one is through phone and video calls.

One thing that this pandemic has made crystal clear is that all of the systems in this country are failing us — from healthcare to education to housing. While we need to keep advocating for changes to the policies that harm us, this guide is titled after the reality that at the end of the day, we must keep ourselves safe. We need to look out for each other and create networks and systems to help each other weather this pandemic. We can advocate for our loved ones in the healthcare system and create mutual aid networks to make sure all of the people in our community get the care they need.

- Any individual in the household with significant medical history or who is older than 60 years is considered at high risk.

- Precautions should always be taken when going out in public by using masks and handwashing.

- If elders are living in the household, it’s best for children to shelter in place, as opposed to attending school. If children attend school, however, make sure wearing masks is required at the school.

- If your child’s caregiver is elderly or an individual with a serious medical illness, both your child and caregiver should wear masks. Also, limit your child’s contact with other people.

- If you have a large number of people living in your household, don’t assume that being indoors at home is safest. Utilize all the space you have available to you to get distance and prevent spreading the virus. Consider outdoor spaces like a yard, a stoop, a rooftop or nearby park to get some distance between your household members.

- If it’s not feasible to utilize outdoor space (if the weather is too hot or cold), be sure to have good ventilation indoors. Open windows and use fans to get air moving so that virus particles aren’t hanging in the air.

- Indoor gatherings should always be avoided, but if you do have them, do the following.

- Get proper ventilation. Get air moving by opening all windows to improve airflow. You can also turn on fans in the room.

- Limit time spent indoors. Less than an hour is best.

- Try to limit the number of people involved.

- Lower the humidity with a dehumidifier.

- Wind Tunnel Hack: Generate a wind tunnel with the Indoor Wind Tunnel Hack. You will need 2 box fans. Place 1 fan in the window so it blows in fresh air from outside. Place the other fan in a second window so it blows the indoor air outside. Ideally, the windows should be on opposite sides of the room.

- Outdoor gatherings should be limited and follow your local guidelines, but should always be distanced by at least 6 feet with all parties wearing masks.

- Get tested for COVID-19, if possible.

- If the child is in school or exposed and not quarantined, we recommend isolation of those at higher risk or elders within the household until 14 days from the time of suspected child exposure. This includes using separate bathrooms if possible, sleeping in separate rooms, practicing distancing, and using masks.

- Monitor cdc.gov or call 800-CDC-INFO (800-232-4636) with questions as this is a new virus and guidelines are evolving.

Make a plan with your family to protect the more vulnerable members of your household.

- If children are going to school, wear masks in the household. (Refer to the COVID-19 and Kids section for additional information.)

- If someone in the house works in an environment where people aren’t wearing masks or there isn’t good ventilation, wear masks in the household.

- If someone tests positive for COVID-19, know how you will isolate. Have this discussion with your family and make a plan before someone gets sick.

- Understand the other environments people are in besides work and school, like associating with neighbors and going for services, to better understand the risk of exposure that members of the family face.

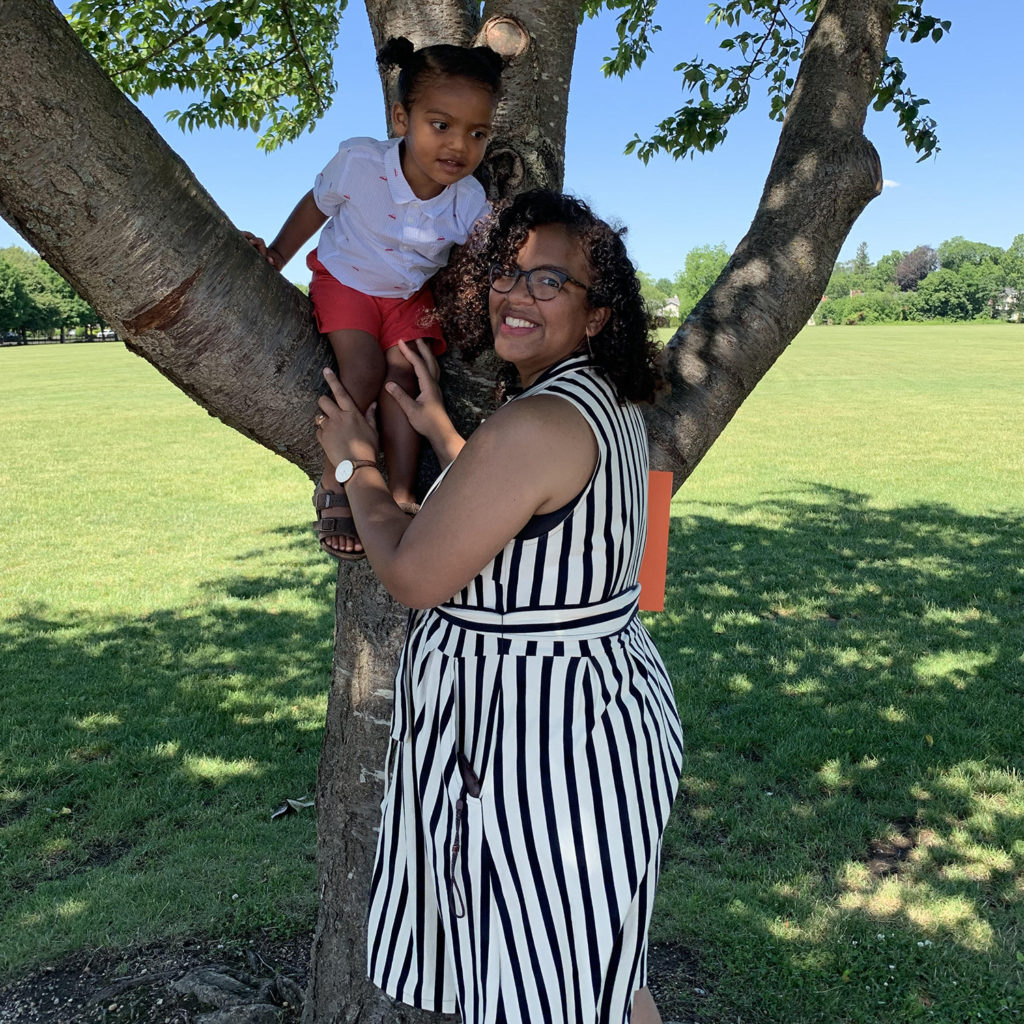

As a family medicine physician, I see a wide age range of patients, from great grandparents to babies. One thing that is very common with my patients is that some of them live in multigenerational homes. For the last few months, we have heard how difficult it is for folks to socially distance themselves when living with many different generations in close quarters. It’s especially hard when small children in the house go out and interact with other children at the playground or at school or daycare and then come home and spend time with older, vulnerable grandparents. An asymptomatic child can easily infect a vulnerable, elderly grandparent. But there are also some important benefits that come out of multigenerational homes. Having multiple generations in the home protects against the detrimental effects of a pandemic on people’s mental health. I’ve seen an increase in admissions of psychiatric patients, with folks going through so much mentally during COVID-19.

Having multiple generations in the home protects against the detrimental effects of a pandemic on people’s mental health.

For adult children, knowing that grandparents are at home watching the younger generation is very comforting. It is very reassuring to be able to offer this sense of normalcy to our children. Also, growing up with grandparents offers a rich sense of identity that children might not otherwise get from family members. Still, one of the key questions that parents should ask themselves when deciding how their kids should social distance from their grandparents is how much interaction do you want the kids to have with their grandparents. If it’s really important to you for your kids to spend time with their grandparents, limit the little ones’ interaction with people outside of the home. If it’s more important for you to have your kids interact with other kids their age, then make sure they can be kept away from common areas in the house while the grandparents are there.

Quarantine fatigue is real. Many of our usual outlets for socializing are nonexistent during the pandemic. But the reality is that people need social contact, and some people and families are struggling without it. So we need to find ways to socialize safely (just as sex education teaches safe sex or safer sex, an important practice that reduces risk when choosing to have sex).

When you have little social safety net, it’s difficult to decide what kind of socializing to be comfortable with and what kind of boundaries to set with friends and family. For many, work demands, transportation needs, housing and educational settings make social distancing and quarantining an impractical expectation. Working in essential workspaces and living in frontline neighborhoods keeps us in an ongoing cycle of risk, uncertainty, and institutional and structural harm.

This unjust social distancing reality is further aggravated by aggressive policing of these communities. In New York City, in a 7-week span during New York’s PAUSE order, police made 120 arrests and issued nearly 500 summonses. 68% of those arrested on charges of violating social-distancing rules were Black. 24% were Latinx. Most of this enforcement happened in predominantly low-income neighborhoods.28

We need information, support and empathy during this time to make decisions about our care and wellbeing. Here are some sustainable options infectious disease epidemiologists think might be a smart way to balance mental health needs with physical safety.

Highest risk

Indoor:

- Enclosed, crowded setting with prolonged and close contact with others (Loud music in which people will naturally talk more loudly and are more likely to spray viral droplets into the air is more risky

(house parties). - Hugging, kissing or shaking hands

- Being in close proximity to a choir

Medium risk

Indoor:

- Sitting indoors a few feet away from a friend and having a long talk

Outdoor:

- Cookout where people are touching the same utensils or eating from the same containers

Lower risk

Outdoor:

- One-on-one meetings in outdoor setting, keeping a distance of 6 feet

- Socially distant walk with a friend while wearing a mask

- Having friends and family bring their own drinks and snacks to an outdoor gathering (It’s also safer to have individual servings of food and drinks, so that people are not sharing utensils.)

Very low risk

Indoor:

- Virtual social visits

Outdoor:

- Going on a walk by yourself or with members of your household only

Here are more tips for assessing risk and reducing harm.

- Know what’s happening with virus transmission in your community. Pay attention to the number of new cases, hospitalizations and deaths where you live. You may choose to be more conservative with your social contact than the current recommendations.

- Consider your social contacts’ vulnerabilities to the coronavirus.

- Trust is paramount. You really have to trust somebody and know that they took social distancing seriously to socialize with them, because seeing somebody right now means you’re potentially exposing yourself to their prior brushes with the virus. Have open and honest conversations with your contacts about your level exposure and how strictly you are observing best practices like sheltering in place, wearing a mask and socially distancing.

- Keep social interactions small. The number of households you interact with is more important than the number of people invited from one household.

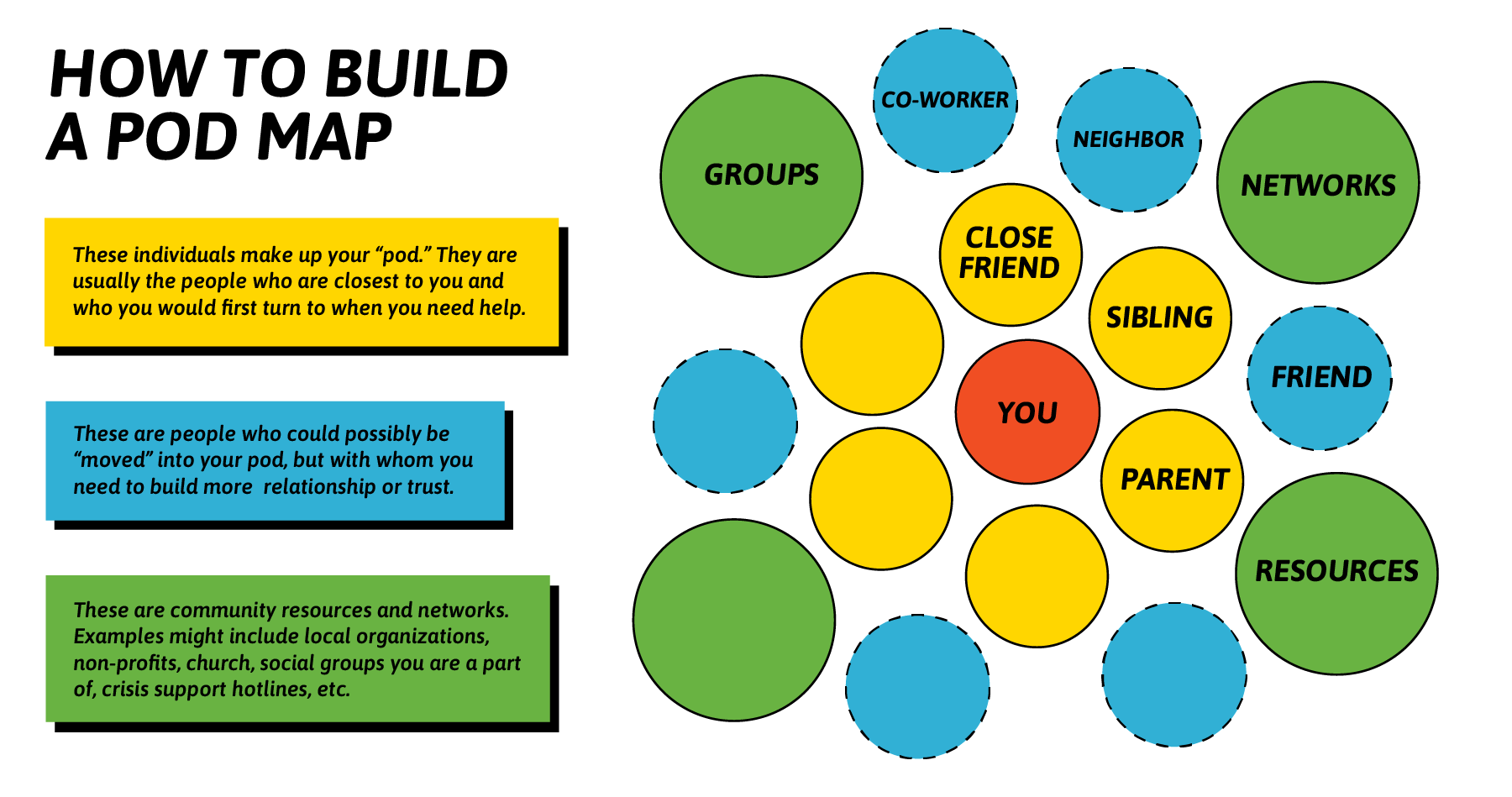

It’s tougher for kids to social distance. One solution is forming quarantine pods.

Quarantine pods make sense for families with small children. It can be tough to have socially distanced playdates, so choosing two or three families who agree to socialize only within their bubble or pod and with no one else is a viable option. In a pod, families hang out together, often without regard to social distancing. Outside of the pod, they follow recommended social distancing rules. See the section on COVID-19 and Kids for more information on planning a quarantine pod.

Our mutual aid network Bed-Stuy Strong, centered in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York, started as an idea on March 12 when I was reading the news about the coronavirus and reckoning with the possibility that New York might be about fourteen days behind Italy, which was then under full lockdown. A few years ago I had determined to never again let the ineptitude and cruelty of the current administration shock me. No, I did not expect much of the U.S. to respond to the burgeoning pandemic humanely or well. I thought of K, my next-door neighbor, who is not in great health, and wondered if he would be okay. Two thoughts danced in my brain: Nobody may come to help us in time; we are all we’ve got. We need to organize, quickly, online and geographically.Mutual aid — that is, reciprocal intra-community help and support expressed in a spirit of solidarity — is the heart of Bed-Stuy Strong, which today is a multiracial network of three thousand people.

After looking to see if what I wanted existed already, I mapped out different ideas: a series of connected private Facebook groups, branching WhatsApp phone trees, feeling increasingly unsatisfied, and then it hit me. Forming a neighborhood-based network on the messaging app Slack would work well to start, and if it made sense, we could set up a phone number for neighbors without reliable Internet access. I built out the Slack infrastructure in about forty-five minutes, with lighthearted channels like #pictures_of_pets, as well as channels for people to share what they needed or wanted to organize around. I made a quick how-to resource in case other people might want to do this for their own neighborhoods.

Staring at the empty Slack, I wondered, What if no one joined, what if people joined and then were awful to each other? I texted my friend these fears, and he very kindly told me to stop being a chump. I ran out and put a note on my neighbor’s door, asking him to call me if he needed anything. My partner and I printed out twenty pages of flyers, cut them up into quarter sheets, and then walked around my neighborhood of Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, putting them up on street corners and bodega doors.