Queer[ing] Family Rituals

The work of queering family rituals is an invitation to closely examine the stories, power structures, and assumptions embedded into how we make meaning of significant events in our lives. It’s also the practice of decentering what is perceived as normal or palatable, keeping rituals that nourish us, rejecting what doesn’t, and actively repairing the harms passed down generationally.

As a faith and justice leader, one of the ways I have learned to queer my understanding of family and rituals is by interrogating the rituals that are part of my tradition, one of which is baptism. While baptism is done in Christian contexts, it is neither original nor exclusive to the faith, but it is a practice that grounds individuals in a lifelong commitment to a spiritual calling. While I was initially baptized for the wrong reasons in trying to acquiesce to the desires of an institutional faith community, I later came to adopt the ritual as a way of affirming my chosen name and gender transition as an acceptance of a deeper calling to intersectional faith and justice. For me, baptism has grown beyond the limited bounds of traditional church and is now a practice of reflection and remembrance of who I am and who I am becoming.

For trans, gender-expansive folks, and queer folks, ritual crafting is not linear or without its challenges. We have made meaning of our key milestones through actions, images, and words, and created ritualization in spaces that have not always been safe or possible. Important to decolonizing rituals is naming where rituals come from, as well as who benefits from their repetition and who has been erased or excluded by them. One example is the ritual of coming out. While a privilege for some, coming out has long been viewed as an appeal to whiteness and cisheteronormative society by Black, Brown, and Indigenous folks who already face multiple dimensions of discrimination and oppression for their existence. Furthermore, in many Indigenous cultures, queer folks were seen as diviners, healers, and gatekeepers to hidden realms. They were not separate or singled out, but known members of the community and essential to “traditional” family structures (see Sobonfu Somé’s The Spirit of Intimacy: Ancient African Teachings in the Ways of Relationships). Coming out is then itself “outed” as a western invention that satisfies only those who can afford to aspire to whiteness, straightness, monogamy, and the like. Queer and trans people deserve more than this colonial framework for accessing and accepting their personhood.

Queering family traditions also studies the colonial, extractive, racist, and xenophobic institutions through which they were developed and challenges the role of power and voice. To decolonize family traditions means subverting authorities that seek to silence, control, or tokenize queer voices. One ritual that has taken back power and liberated communities is naming oneself. For BIPOC folks in particular, naming oneself is both an act of resistance and reconciliation. We resist being forced to fit within a specific idea of who our parents thought we were or wanted/expected us to be. We push back on harmful narratives that do not affirm our evolution and we reconcile what is meaningful and life-giving to ourselves.

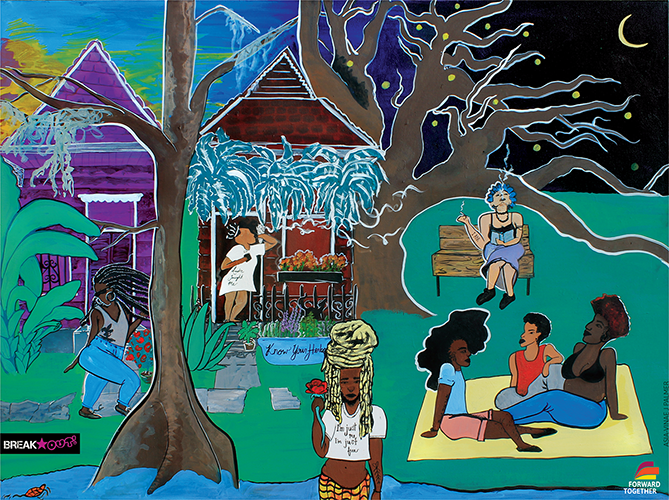

This work is rooted in lineages of care, community, and relationship. Decolonizing rituals means rethinking the words, images, and actions we’ve inherited and how they need to evolve or be rejected altogether if they center capitalism and individualism. Some ritualized forms of resistance that trans and queer folks have developed include creating mutual aid networks, decolonizing intimacy, redefining family, and marking surrogate holidays (like LGBTQ+ Elders Day and Trans Day of Resilience). That said, folks of color have experimented with new ways of making meaning out of necessity and survival, not forsaking the collective work it takes to build and practice new rituals at the grassroots level.

Examples of this can be seen in:

- queer parenting models that include aunties, uncles, auntles, “play” cousins (and not relegating these titles solely to biological family),

- shared living models (folks have done life together in spaces like polycules long before there was language to describe it),

- upending gender roles and stereotypes in marriage, and

- the embrace of non-gendered, non-normative child-rearing

All this has been made possible thanks to historical practices shaped in villages, tribes, and other webs of care where the nuclear family is decentralized. If there is anything to be learned from our trans and queer ancestors, it is that our survival is intersectional and interdependent.

One of the ways family traditions have become outdated for LGBTQ+ folks is through exclusionary language and symbolism. Some stories, images, and objects that are passed down generationally wildly assume heterosexual partnerships, binary gender, or a single lineage. Some examples include gender reveals and wedding ceremonies where colors, clothing, and names are strangely and unnecessarily gendered. These traditions not only harm queer folks by invisibilizing or diminishing their identities within family memory, but undermine belonging. These traditions can also force trans and queer folks to self-censor. What may be a commonly accepted ritual to invoke commonality may do more harm than good. Furthermore, situated within a white western context and assessed against capitalistic and paternalistic values which have never intentionally centered BIPOC communities, these traditions can feel alienating at worst and performative at best.

Other barriers to family traditions include the policing, secrecy, and conditional acceptance we get from cishet relatives. Through social mores like not airing “dirty laundry” in public or making certain conversations off-limits, families of origin create undue emotional labor and put a heavy tax on trans and queer folks. Additionally, there are rituals where LGBTQ+ family members are expected to defer, stay silent, self-censor, or risk excommunication. These acts of isolation can create anxiety and fear, alongside the risk of being outed or punished – especially around holidays. Family traditions are therefore deservedly held that much more closely under the microscope of colonization, because they have the potential to turn rituals (which should be practices of affirmation) into sites of surveillance and shame.

We begin undoing the harm done by broken family traditions by first queering what we mean by “family” and unpacking what is salvageable. In the western context, family has been synonymous with nuclear family or those who are born into certain blood ties or biological units and protected by certain laws or statutes. The work of decolonizing family means divesting from the ideology that family exists solely for and among those with whom a person is biologically related. Under this precept, the burden is disproportionately placed on individuals who may make decisions about a family member’s autonomy and access to care based upon their own understandings and preconceived notions, and not necessarily what is in the best interest of that family member. We can subvert this by institutionalizing autonomy and care as prerequisites for how we engage with others, regardless of blood relation or familial affiliation, and prioritizing communal rhythms of life.

To institutionalize autonomy and care means accepting the multiplicity of ways we show up for one another in spite of oppressive biological family dynamics and state violence. Trans and queer folks are well-positioned to lead our cishet counterparts in creating new rituals that lean toward an expansive definition of care and autonomy. We can nurture care through chosen family, kinships, and other community inventions that refuse to adopt or perpetuate isolation and fear. It also means pooling together material resources to survive the end of capitalism. The stakes are too high for us not to develop mutual aid networks that are expansive and sustainable in meeting our everyday needs. Simultaneously, we can learn from the Black Panther Party to do the hard work of teaching what is at the root of these systemic failures and filling in the gaps where the state has left our most vulnerable. Finally, making autonomy and care real means shifting away from punishment and towards mutual accountability. The disability justice movement reminds us to value interdependence and make care a shared responsibility, not an individual burden.

Prioritizing rhythms of life in the collective sense is harder but no less rewarding when we consider the ways family has been colonized. We desperately need to release our communities from the fascination with and blind acceptance of cisheteronormative rituals. The truth is that family rituals can be powerful tools for personal and collective transformation. But if a ritual is not life-giving, decolonial in practice, and not designed with reciprocal care and collective accountability in mind, it should not be adopted into any family framework. The rituals we practice must instead:

- Be accessible and expansive

- Center affirmation

- Make explicit invitations for participation

- Establish clear norms around consent

- Honor dignity and joy

- Decolonize ceremony for the sake of tradition

This list is non-exhaustive, as I’m sure there are more best practices that my siblings and relatives could add. The invitation is open and the time is ripe for us to co-create together what we feel would best serve our desires and destinies.

The future of family rituals looks promising should we take the work of queering seriously.