Kin or “To Kin”: On Ungrammaring Family and Freeing Care

The family isn’t dying. It was dead on arrival.

Killed when relation was calcified into form, a grammar of the world. What we call family is only the fossil of relational abundance. And we’ve been subsisting on its carcass like lost travelers in the wilderness desperate to survive.

In 1965, Daniel Patrick Moynihan issued a scathing report2 that blamed black single mother households for black social illegitimacy and our perennial socioeconomic inequality. Not racism and its pervasive legacy. Not even implicit bias. Once blackness was grammared as pathology, “family” became the preferred site of reform and blame. This structural gaslighting, much like the tale of black-on-black crime, became an internalized leech on black social uplift consciousness. It unleashed this never-ending narrative logic that black families are broken. Ebony and Jet magazine were critical in setting the black agenda and in 1983, a cover was released sparking a new conversation—”The Crisis of the Black Male”—where black poverty was on the rise and people were cynically blaming “welfare queens.” From then on, the nauseating discussion became ubiquitous, especially in discussions involving gendered dynamics.

Blackness, in America specifically, was built in response to whiteness. The black body, once stolen from the homeland and carted on dangerous ships in abhorrent conditions, became more like produce. Fungible, perishable, endlessly replaceable. It lost its humanity and became a commodity. An extractable resource. Blackness was forced into legibility—flattened into an image whiteness could digest. What was once a beautifully unmanageable, queer condition was under threat of containment. Where “black love” campaigns held a secret message of what love is affirmed and what those families should look like. Where we became more interested in casting intracommunal blame for the phenomenon of the absent black father and the welfare queen and less concerned with building care and support networks that validated and affirmed all bodies and their varied formations and conditions. Whether ancestral or reactionary, our family models became the focal point of the social conditioning project designed to kill the black body. Where our very ideas of who we are as human bodies, as “men” and “women,” were dictated, assigned, and enforced. And it is in the family structure where this took hold. Where we act as agents of the state to regulate our bodies. To name what a woman’s role is and who the leaders are. Black families, with their very multiplicitous formations in contrast to the white, nuclear family model, became the problem. And the structural conditions that propagated socioeconomic inequality as a result of a societal ethic where care and support need the family—in a particular two-parent, heterosexual formation with particular white bodies—were ignored. This assimilationist performance of aspiring to replicate the standardized family model and castigate alternative formations became the black neoliberal stain in our relational fabric. Instead of being sites of care and improvisation, the black family was contorted into the state’s project. The crisis was never the black man or the welfare queen—it was always family itself, distorted into grammar. The accepted syntax of kinship under capture.

“The family” is a foundational unit in the common grammar of the world. Grammar here is important, signifying the whole system and structure of language and understanding to formulate the common sense. Grammar is a regulatory prescription, the guidelines through which we all participate. But grammar isn’t fundamental or universal. It can be undone. The theorist Hortense Spillers writes often about syntax and grammar, particularly as it relates to blackness and the black body. In her brilliant essay, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” she writes, “Slaves shall be reputed and considered real estate[…]I emphasize ‘reputed’ and ‘considered’ as predicate adjectives that invite attention because they denote a contrivance, not an intransitive ‘is'[…]The status of the ‘reputed’ can change, as it will significantly before the nineteenth century closes.”3 We were made into property. Not by essence but by syntax. And that syntax could shift when the economic conditions changed. Blackness, gender, family—all can be “reputed” and “considered” into being. Which means: they can be un-written. Refused. Shattered.

To know and move within “the family” is seen by many as simply fundamental. An innate function of society. We struggle to accept or even consider the abolition of family because who we love, how we love, and who we are at our core is so intrinsically tied to the fable of the family. We couldn’t imagine embracing an ideology that would sever our most intimate connections, even if those connections are poisonous. We do it all for our families. We will hurt, harm, or betray for our families because they’re all who matter to us. Billionaires amass wealth and exploit resources to the detriment of the 99% in the name of their families. Legacy. Lineage. Empires. And we justify this selfish, individualistic behavior because we are agents of the family unit where exploitation is turned into duty. This is just how it is, right?

The late theorist Mark Fisher responds to this fatalistic “common sense” with a brilliant idea called ambient discontent. It’s the ache that feels like truth, the hum that lulls you into accepting your cage as a cocoon. It’s background noise. Accepting the world as “normal” but never interrogating whence normalcy derived. You aren’t happy and resent the conditions around you but you press onward with that dull ache. And you mistake that ache for reality. You start believing this is all there is. “The vividness and plausibility of this miserable world—with misery itself contributing to the world’s plausibility—somehow becomes all the more intense when its status is downgraded to that of a constructed simulation,” he writes. “The world is a simulation but it still feels real.”1 And in the simulation, misery is depth. You suffer, therefore you are. You grind, therefore you deserve. Ambient discontent makes the simulation of family feel natural.

But this is a zombie logic. A logic that hinges on the regulation of the human condition and submission of those bodies into form, or rather, a zombie form. The way that humanness, not to be confused with humanity, has been grammared, or constructed, into our psyches is a death contract. Not death as a complement and continuation of life but as the antithesis to life. By this, I mean that constructed reality and collective consciousness hinges on our commitment to consuming ourselves and others. So much so, that we are but decomposing shells of ourselves. Society becomes a machine of forced proximity—bodies made to coexist while decomposing. Not alive, not dead—just endlessly dying. A zombified intimacy. And it is through the family model that this intimacy is folded into commodification. Suffering as pseudo-life. The world we’re inside is both fake and all we know. Humanness becomes a fugue existence necessitating collective hallucination, experienced as reality even when unreal. That makes it hard to leave. Not because it’s good, but because it’s so convincing. Not love, relation, and care—but their regulation through the concept of family. Not life itself but the making sense of life through regulation.

Once something becomes grammared in the nounic state, to be calcified from experiential to extractable, it is rendered dead. Nouns are always pictures. Illustrations. Only snapshots of what was living. “Family” is the conceptual extraction. Where relation becomes form and rigidity takes hold over what should remain in flux. Capitalism weaponized what grammar has already killed. A grammar that turned trees and plants and interconnected systems of nature into coal to be commodified. What we are seeing capitalism do to the family is what we see industry do to the coal. A coal formed from fossilized relation through a conceptual grammar that precedes capitalist extraction. A grammar that calcified life into a commodity. Coal is the dead remains of life. Of forests, fungus, time, heat—compressed and silenced and rendered usable.

Family values arguments are the cultural necromancy that animates the corpse of the family to police kinship. Family reproduces property, race, trauma, function. It is the gear keeping the white imperialist meaning-making machine running. To advocate for queer formations or uplift alternative modalities outside of the nuclear modal are met with claims of the “attack” on the family and a need to reassert family values. The “family” becomes the cadaver through which values (deeply personal beliefs or ideals) are the contagion consuming our bodies into submission. What is personal becomes political by design—one that imposes external definitions of your values (as is the case with “family values”) and strips self-determination. This social manipulation blurs the line between personal belief and expectation. Are my preferences really my own or were they constructed? The struggle intensifies as the state prescribes the shape of our values—mandates we internalize as self-evident truths. Thus, we find ourselves grappling with the paradoxical bastardization of “family values”—a weapon wielded to justify exclusionary policies, from anti-LGBTQ+ laws to reproductive restrictions.

Family is not the root of society. It is the spell cast to make a specific type of social arrangement feel natural. A two-parent, heterosexual unit serves as a modal agent of the state, shaping and constricting a child through heteronormative conditioning. This not only intercepts natural childhood development but also limits the possibilities of embodiment, demonizing non-conforming modalities. Societal acclimatization through normalized family structures is less about affirming children—it’s about conforming children to a rigid, constructed model of gender, sexuality, and family that upholds existing power structures. That keep the show on the road. Failure is ascribed to the parental unit and the child for not meeting the goalposts in the project of heterosexuality. We blame the existence of a transgender girl on the fact that she did not have a father or that her father was “too soft.” The protection of the family becomes a campaign to cement the illusory permanence of a racialized—generally white—cisgender, heterosexual family model. How we relate to one another, how we ascribe value, who is worth protecting, who deserves to die—all connect to the symbol of the family.

Family doesn’t need to be responded to—it needs to be re-understood as a motion, a pulse. An ungrammaring. We have an opportunity to unbind relation from syntax. To release our formations from the prison of legibility. It is only through this commitment that we are freed from the hallucination. Where the illusions are made clear and we are given permission to unfurl, be curious, and seek out a new grammar of existence. This work may not feel immediately urgent until we recognize all of the myriad of ways that the opposition has successfully chokeheld culture and erected an ideological fortress that blocks access to the reins of meaning itself. Because they’ve been able to set the terms for understanding, we’ve devolved further and further into a horrifying pit of polarizing political warfare. They’re able to latch onto our imaginations and exploit the weaknesses in our constructs, pervert them even, to justify their abhorrent behavior. It is the family whom they protect. The family whom they defend. Family as the institution. We must bury the carcass that can be hollowed out and automated to justify colonial violence—hierarchy, exploitation, gender discrimination, wealth accumulation, xenophobia, anti-blackness, restrictions on abortion, fascism, closed borders, transphobic violence. We see it in the abduction and disappearing of humans, the funding of a genocide in the name of erecting an ethno-state, the legislation of bodies out of public life, the funding of police and prisons over investments in care infrastructures within communities, the naming of empathy as “the fundamental weakness of Western civilization.” The list is endless. And it all comes down to how we understand relation to one another on a fundamental level.

Family is post-nounic. It is an act. A state of being in community with everyone around us. Abolition of “the family” doesn’t mean no relation. It is the freeing of care. A care that has no bounds.

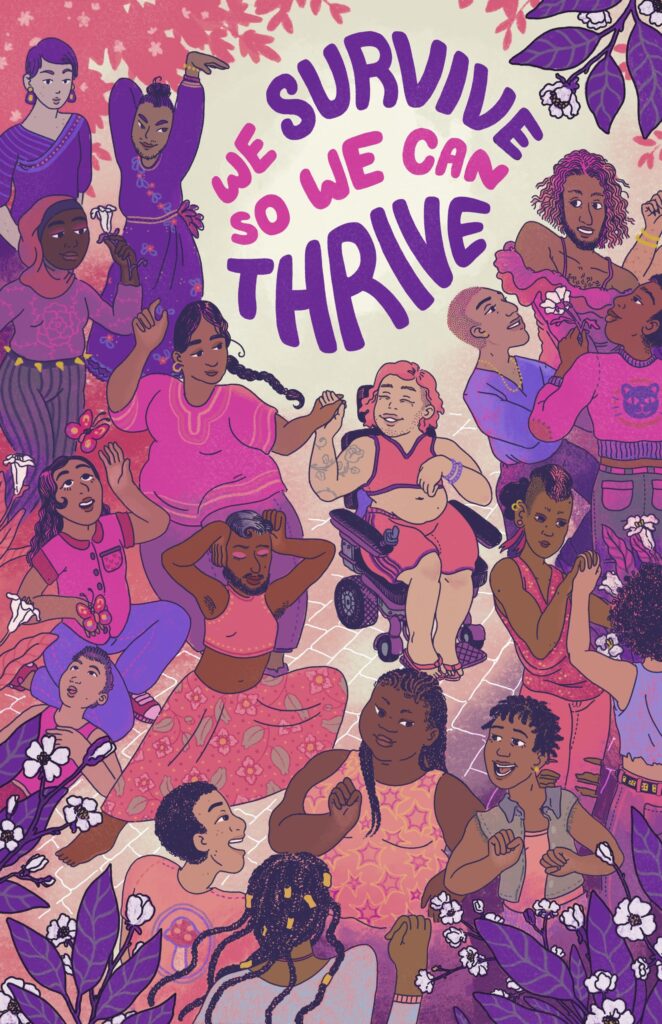

The world is dying and in order to save it, we must move away from the violent extraction of fossil fuels into renewable energy. From coal into wind power. From “family” into transitivity. If end-times fascism is a celebration of destruction, transitivity is the quiet revolt of becoming. An unbinding ethic of kinship. Our fight should be toward a non-definition or, more aptly, an undefinition—one that affirms all sorts of expansions of formations and dynamics so as none are more or less intelligible, comprehensible, or valid. Formations that affirm chosen families, indigenous kinship, and even cooperative parenting. Success may feel like failure. Like falling apart. Like emptiness. Like unreadability. But that’s how we know it’s working. How we free ourselves from the shackles of the common sense/logic of family. This is our renewable energy. A kinship that flows like water, whips like the air, containing multitudes. Abundant and improvisatory.

Family should be an abundant texture felt like the wind in the air, but it’s been packaged and sold. Entangled in a societal need for legibility—to standardize experience and capture care. It’s never been neutral. It’s been captured by syntax and imbued with symbolism. Our job is to bring humanity back to collective integration, to life. To expand the limits of our imaginations of family beyond what it should look like and towards an expansive and abundant experiential model. An embodied feeling of family beyond legibility. We need to call ourselves back to modalities of care that preceded the colonial invention of family as a unit. We must radically re-envision how we relate to one another that doesn’t require necromantic consumption.

The concept of family as an institution has always been dead, a carcass misrepresented as kinship. Our task now is to cremate it and spread its ashes to let care networks breathe again as renewable, unbound, and free as the wind.

References

- Fisher, Mark. 2016. The Weird and the Eerie. N.p.: Watkins Media.

- Moynihan, Daniel. 1965. “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action.” U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.dol.gov/general/aboutdol/history/webid-moynihan.

- Spillers, Hortense. 1987. Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book. https://www.mcgill.ca/english/files/english/spillers_mamas_baby.pdf.