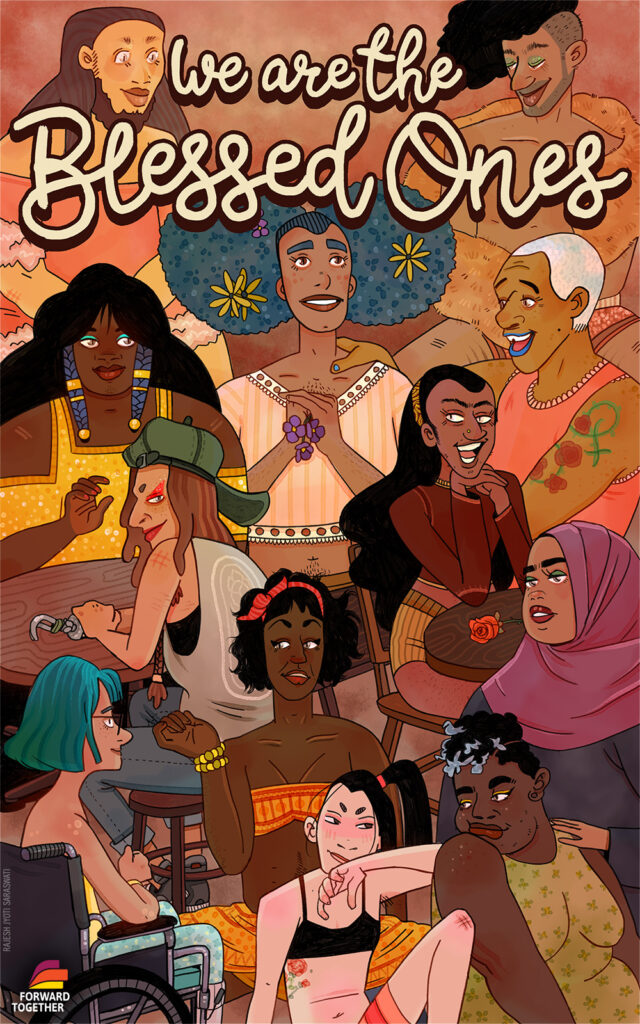

How We DO Expansive Care

Rarely, if ever, are any of us healed in isolation. Healing is an act of communion.

– bell hooks

When I was younger, I used to think that caring for people was ideally one-directional. I am supposed to have my stuff together and be available for others to fall apart emotionally, financially, physically.

Mia Birdsong would say, “The American dream is about individualism and independence. It’s also a kind of performance, right? It is a performance of invincibility and having your shit together. And if we’re performing that, and our sense of self, our sense of being a successful person, is dependent on other people believing that we have all our shit together. Then we can’t be known to each other.” And I deeply desire to be known.

I am a community builder in the Southern tradition. I pour into people through feasts, helping people fix up their homes, giving rides to the doctor, offering a warm bed when home doesn’t feel like home, and I babysit while people protest. What I enjoy most is weaving people to each other. “Oh, you’re into what? I think you should meet my friend.” People have found best friends, business partners, and spouses through my special interest. I help people be known to each other.

Intimacy is a central component to how several of us give and receive care at Forward Together, so I interviewed colleagues to offer some portals of possibility to you, dear reader.

KELLY – TO BE KNOWN IS TO CHECK IN

To be known by someone means they have shown you cultural humility and emotional safety. For Kelly these traits can be developed in small, daily ways like checking in via text. However, she offers important considerations. Scan your phone: are you only proactively reaching out to your closest connections? Is it just your given family or best friends? And when you do message someone you aren’t as close to, does that mean you have no idea what’s going on for them? Is the text more generic? One way to be known is to know what’s going on.

“It feels like so much labor sometimes, but it does make me feel cared for and seen when someone checks in on me,” said Kelly who currently lives far from most of her given family and is growing new kinships locally. “Our lives are just so full with things that we’re required to do for work and things that we want to do that are personal interests. A lot of us have family ties,” which all connect to obligated allotments of our time. With such limited capacity to show up for other people, capitalism teaches us that showing up for “non-nuclear family is the extra.”

Texting friends and community members is one way that Kelly said she unlearns the static prioritization of biological relationships and brings other beloved community to her core.

“What I’m realizing is – it’s the small moments and the day-to-day moments. It’s remembering the tidbits people share with you and following up with a text. ‘How did your interview go?’ Those are things that are important to me, because I feel like we’re so distracted overall. We remember the big stuff, like if somebody’s getting married, or if someone’s having a kiddo, or there’s a graduation, but it’s these small, everyday moments that make us able to connect. Knowing how somebody is feeling, being able to empathize, and dropping a small note here and there is what I feel solidifies these kinship networks.”

The sentiment “thinking of you” goes a long way for a lot of people seeking belonging. Something else Kelly does is have cards stocked up to send whenever someone comes across her mind.

“A really simple thing is buying greeting cards from different places that have some sort of significance. Every now and then, I’ll pull one out and mail it off or send it to somebody. ‘I was thinking about you.’ Ugh, that hits me in my soul and my heart, and that’s what I would want other people to feel.”

LEO SEYIJ – TO BE KNOWN IS TO BE WITNESSED

When Leo Seyij reached out to his chosen family about an upcoming medical procedure, he knew he would have a better experience with being vulnerable than he had years ago. Back when he was 17, being outed didn’t feel like being known. There wasn’t a sense of belonging – from family or spiritual community.

Not having to depend on his given family for care this time allowed him to process what was happening within his recovering body and with the chosen caregivers around him.

“I had a network that included a couple of good friends of mine, who I definitely see as family now. My partner at the time. I had a therapist. I had my spiritual community. And all of these people that I leaned on as family because my given, biological family was not either unable to, or refused to [care for me].”

His caring kin exercised with him and encouraged regular mind-body practice. They role-played setting boundaries with his parents and anyone who had questions or opinions about his transition, his bodily autonomy, and his decision making. “It provided a level of intentionality and intimate care that I knew that my bio fam couldn’t give me.”

Building these deep, restorative relationships took time, and many of them began during Leo Seyij’s spiritual journey in seminary. In school, Leo Seyij was able to bond with people intergenerationally for the first time, particularly with an elder who embraced identities of his that caused tension at home. They and a few others gathered regularly and shared “the vulnerable sides of themselves. I think that’s what has allowed us to stay close knit. We know those deeper parts that sometimes are socially unacceptable to share.” He was witnessed and got to witness people in their spiritual and emotional growth.

I’ve been through some shit,

he said.

Growing up, care was tied to the obligation of family. In these collective spiritual mental health spaces, caring was reciprocal, non-judgemental, and by choice. Without the tie, “You’re able to upend destructive and oppressive patterns and behaviors,” like self-repression and respectability.

“We were able to challenge one another in healthy ways about our theology, about what we believe and why we believe it, about what it is that we’re called to do, about what does a vocational career in ministry look like…and what are inventive ways that we can live out our lives that may not necessarily reflect the same structures, or the rigidity that we grew up with in the institutional church?”

They asked questions that would not be allowed in Leo Seyij’s childhood church. These were the safe spaces to bring up doubt, which in turn strengthened his faith in God and in himself. Doubt that God would be so rigid given the infinite possibilities of things and people that exist. Doubt that God would give free will, but not bodily autonomy. Faith that God trusted his next steps, which was ordination.

“Ordination is done in community.” There is an outer collective journey that maps onto the inner journey you’re on as you discover your purpose and offer to the world. It requires a “collective discernment that says, ‘We see what God is doing in and through you and we want to honor that.’” Leo Seyij made sure that his ordination was rooted in the faith he had honed with the kin that influenced him, including atheists and Muslim imams. “And my bio fam was there to witness and learn what my chosen, new family already knew about me.”

What Leo Seyij loved most was that his chosen family worked to ensure that this was his ceremony – not his parents’ ceremony. His biological family didn’t have a role other than to witness Leo Seyij be adored.

Leo Seyij continues to co-host witnessing circles so that he and others receive the mental and emotional resilience that comes from belonging to a people.

CHAKIARA – TO BE KNOWN IS TO BE BOUNDARIED

I’m a Black single mom in the South. I rarely receive care, but I’m always in a position to caregive for others.

ChaKiara connects with other single moms on social media and they exchange emotional encouragement. One online friend “will always slide into my DMs, or slide onto the comments, and reaffirm me, and kinda put a mirror in front of me. Like, ‘Hey, you don’t see all these beautiful things about yourself? You are deserving of love.’”

For caterer, organizer and past “people pleaser” ChaKiara, being known correlates with having your capacity respected. “We have to create boundaries, even in our big hearts,” she said.

In pursuit of that, ChaKiara is collaborating with a local group to start a food pantry. Creating a pantry or a free99fridge is a way to have multiple people help. ChaKiara is able to show up when she has the capacity and bow out when she doesn’t. It’s a shift from the stress of giving more than she can out of obligation or feeling like she’s someone’s only hope.

For ChaKiara, this abolitionist approach to care – one that doesn’t require close relationships – works for her. “It’s easier to care for people that I don’t feel forced to deal with. Because I don’t necessarily know all of their business, all of their history. We don’t have a fragile, traumatic history. It’s easier for me to just know some superficial things about people and still be able to care for them.”

ChaKiara said the food pantry is responding to a growing need. She already gives free meals to college students on a regular basis through her NAACP chapter. However, rising unemployment, housing costs, and inflation have made the need even greater where she lives. Local social media groups are filled with vulnerable stories from people living in their cars. A shelter near her doesn’t accept children. The one that does has a waitlist.

“So people are living…families…single mamas and their three and four or five kids are living in their cars in the parks. How do I help them, right?”

OTHERS – TO BE KNOWN IS TO SHOW UP

Several other Forward Together members briefly shared what they do to expand their care beyond family and towards community. All of the interviews tie back to one central point – direct connection is key to our thriving. The relationship doesn’t have to be deep to be worthy of care.

L’lerrét has started volunteering with HOSPICE to support people through the end of life. Aen is a co-steward of Trans Closet Club, which offers free gender-affirming clothing to folks in Oakland, CA.

Ally celebrates friendship anniversaries with the same intention and investment as a romantic anniversary, which includes trips, dates and giving flowers.

Someone anonymously shared, “I don’t necessarily know how to give care, so I’ve had to learn a lot from my friends. I don’t think we live in a country that teaches us it. I think things like friendship and care are learned behaviors, and I think we need to teach people how to do it.” Ally does that by “proactively creating and sharing care plans with chosen family so we know how to care for each other in times of crisis.” Several of us have also created relationship maps to illustrate who we rely on in times of need. Ours were based on Mia Mingus’ work on pod mapping.

Expanding care beyond chosen or given family makes care more reciprocal and more sustainable. From Leo Seyij’s church, ChaKiara’s food pantry, Aen’s closet club, to L’lerrét HOSPICE work, these collective offerings of care allow folks to receive the care they give when needed. A wide network of relationships at various depths makes it easier for folks to tap in briefly and give primary support folks a break.

In fact, this is what this whole anthology is about. We want to be known. We want to give and we want to be able to receive. We want to be known as people who are experimenting and failing towards a beautiful, interdependent “something else” beyond our wildest dreams. It is our hope that you feel inspired by getting to know us through this anthology to try alongside us.

Thank you for reading this initial collection of what can be.