Disaster (Survival) Makes a Family

Beat One

We are fragile, tiny people, us.

Journal entry on Saturday, September 3rd, 2005.

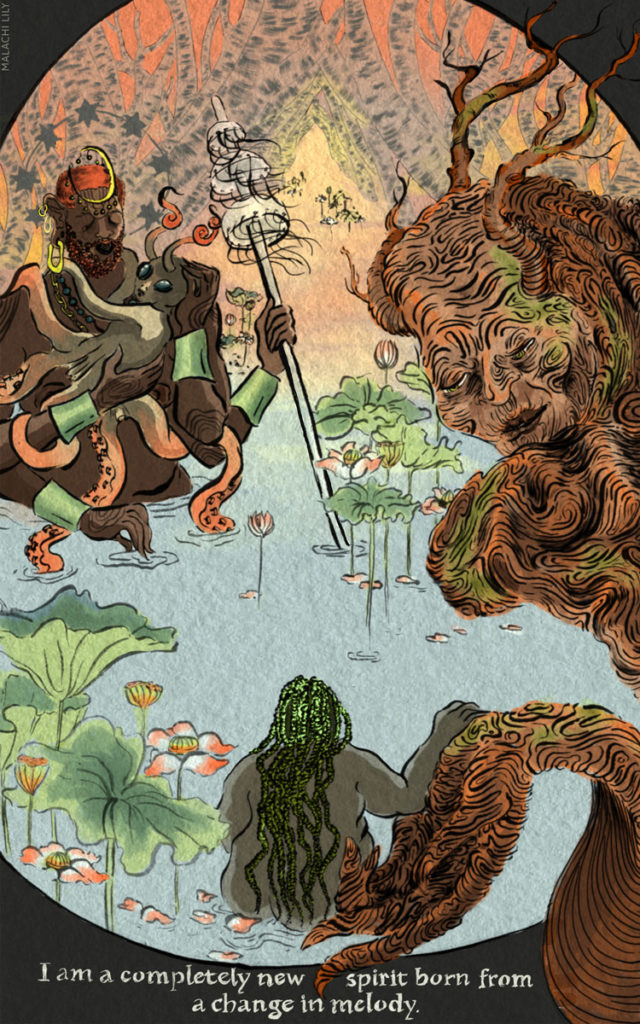

“We” was my family. Or at least the unit of people that the government considered as my family, legally by blood and marriage. My spouse, our child, and me. This little trio, with our one-year-old cat, had evacuated our home in New Orleans, Louisiana the Saturday prior, ahead of what would become a mandatory evacuation for Hurricane Katrina and the subsequent, years-long, man-made disaster that followed. It has been 20 years since the day the storm made landfall and the levees broke (or were blown), but each day these past few weeks marks another horrible two decades. Two decades since the Danziger Bridge shooting (September 4th). Two decades since the militarization of the Gulf Coast, since the suspension of the Davis Bacon Act labor protections (Sept 8th), since the shuttering of public housing developments, since the firing of public school teachers. And over those weeks, the accordion effect of the state compressing who we could be as a family, as a city, and our chosen kin resisting, expanding, pushing back against the erasure and denial of who we mean when we say “we.”

What stands out to me from those journal entries and the impossible efforts this year (and in 2010 and 2015) to commemorate everything that we lost “after the storm” is the great collectivizing experience that it sometimes was, that it could be. When the state legislated how families should be through the various disaster relief efforts that said only certain relationships (by blood or legal marriage) would be recognized and compensated, or when the state failed altogether by not providing food, water, and shelter, people came together and created new bonds and affirmed existing ones that weren’t always explicitly recognized. Collective meals, sharing homes, giving each other clothing, mourning together and affirming what we knew was really happening in the face of government denial, of so much state violence and neglect. We shared horror at the reveal of this country’s power holders’ rancid disregard for human beings and the city that was an allegedly beloved cornerstone of what is considered “American” culture. Because many of those human beings and the culture of the city were Black. New Orleans in August of 2005 was a Black city. And the culture, history and vibrant lifestyle of this city, all of it was owed to the Black people who built it. Or to quote phlegm, “Everything you love about New Orleans is because of Black people.” But repeatedly in the history of this country, when there was an opening for us to collectivize, to see our linked fates or shared path to liberation, racism–and specifically anti-Blackness–was used to thwart these efforts.

Beat Two

Who “belongs” to the American (dream) family?

These disasters remind me of that adage I heard constantly, “Family is the most important thing.” When we evacuate, we are supposed to take the most important things. Growing up in Miami, we were used to preparing for disaster very casually. Later on in New Orleans, it was similarly a “throw a few things in the car and go stay at a friend’s house” type of thing, to avoid street flooding and what could be many days of power outages. Across those eras of my life, family looked different. In the immigrant single mom-headed household of my childhood, it included extended, non-biologically related kin, folks recently arrived, or literally found family after being long lost in the migration process. In my early adulthood, my usual queer and trans household was my boo and/or housemates, the people with whom I decided whether to stay or go. Before I had a kid, “family” was always equated in my mind with “your people,” and it felt very loose, even during the scariest storms: Andrew, David, Hugo. Before 2005, I never felt responsible for bringing a particular scope of people to safety.

But in the urgency of Katrina’s approach, with a mandatory evacuation impending, my first responsibility felt like it was to the family that the state had defined for me through birth certificates, through tax forms, through medical insurance, through the limited resources we had access to when it was just about a paycheck and a form. My family was, in that moment, my child and my spouse. Before the disaster, before this imposed selectivity and crisis mentality, family had more room, more people. We had other family. We had neighbors. We were part of a tight-knit community. We were not raising our kid in isolation, nor could we. One of the things my partner and I often said to each other was, “Two parents are not enough.” And even now, divorced, many homes, relationships, and evacuations later, as co-parents supporting a young adult, we rely on an extended network of close friends who love and provide care and have shown up for us as our family.

In the weeks and months from the moment we decided to evacuate, it’s the “thing” part that sticks out to me in the adage about a family being the most important “thing.” The family as property, as something that belongs to you, that you feel ownership over, as opposed to family as something that you have a sense of belonging with or people with whom you have a shared responsibility. I wonder about that distinction both in my family of origin, in my chosen kinships now, and in the history of the United States, and generally empire and colonization of the Western Hemisphere, because something about it all feels related.

I was in grad school in 2005, studying Cuban family relationships, as represented in literature and film, that echoed the identity of the nation racially, politically, and sexually. The “founding narrative” as it is called, was very similar in Cuba to the US. The family was the “landowner” (the master) and his wife and their children. For legal, social, and political purposes, they were defined by a relationship to property, to land ownership, and to owning human beings. The reality of the founding of the United States and Cuba included the enslavement of Africans/Black people who eventually were blood related to the master through his sexual violence, which the state not only protected as his right, but incentivized through capital. For years, a husband could not legally be accused of raping his wife, even in legally sanctioned matrimonies, because she was also his property. This is not to conflate them, but to ask, does ownership, belonging, family as property mean you can harm and do whatever you want to someone without consequence–indeed, be incentivized to harm? For so many of us, family is the place where we first experience harm.

New Orleans felt resonant for me; echoes of Cuba resounded here. New Orleans, a place many see as a living entity, had experienced the harm of that dual “family” definition: of being a part of a larger “we,” but subject to harm committed with impunity. Katrina revealed the reality of the racial hierarchy. The way that the city was treated, the way that people accessed resources or didn’t based on their membership in a family, was absolutely racialized (and also had everything to do with their gender identity and sexuality.) But on a larger scale, in what I would argue was (at least briefly, across the globe) a unifying experience, a repudiation of the horror of racialized violence and neglect could be done justifiably to the city, to the Gulf Coast–because it was a place with inextricable, deeply rooted associations with the antebellum South and with the resistance, joy, and power of Black American liberation struggles.

Collectively, New Orleans, in its resistant and persistent Blackness, was revealed to not be part of the family.

Beat Three

Us versus Them versus Healing

History matters here. It repeats, it echoes. My parents left Cuba in 1967 under circumstances that remain nebulous to me because of multiple conflicting narratives from a variety of family members, but the unifying thread was that they needed to get out in a hurry and they did. From one day to the next, with whatever they could carry on the plane, my mom, my dad, and my five-year-old brother left and would not return for decades. My father never returned. When the boxes of secondhand clothes that strangers and friends shipped to us arrived at my mother’s house in Miami, she sat down suddenly, clutching her stomach. “I never wanted this for you. For you to know this feeling, the feeling of having nothing.” It surprised me because she always said she didn’t care about the things they left behind, only the people. To me, we were not the same. But I didn’t realize then how many people we were about to lose, how the tight-knit community would have holes, would never be the same again. There was a rupture and we would have to rebuild. It would take some of us years to return, and even then, we would be changed.

After the storm, the charter school system put families in competition with each other for spots at safe and functioning schools. The family became an individual unit of consumption. Our family was pitted against other families for limited spots at the few schools where conditions were not militarized or prison-like. This was actually a dynamic before the storm too because of this narrative that there were so few “good schools” in New Orleans, and so the good schools in New Orleans were schools that you had to test into. My pre-schooler took a test to get into the school that they would eventually go to. Parents agree to this because we’re already trained into this mindset that “I just have to worry about my kids.”

That dynamic also echoed in the dynamics around alleged “looting” right after the storm–or as I like to call it, surviving. The idea of the sanctity of private property means we don’t want people to take what’s “ours” even if it’s a thousand miles away in an empty house. People are hungry and need to survive. I don’t want people to die of dehydration. One of my journal entries reads, “Hey ‘looters,’ there’s 13 gallons of fresh water in my house at this address if you need it!…My house is not more important than you having water to drink.” Who are those looters? They’re other people–if they are even considered people, since immediately after the storm, a huge part of the Shock and Awe campaign was to criminalize everyone and militarize the city and the whole Gulf Coast. The idea of the family as property, as what “belongs” to you, is used to motivate fear and encourage this “protect what’s yours” mentality. It reinforced the idea of family as this in-group versus the “others,” an out-group that you were in competition with, as opposed to people you were interdependent with: your neighbors, your extended family, your kin that had also survived what you were surviving.

In March of 2020, many of my chosen family members who still lived in New Orleans had another disaster to survive–the Coronavirus global pandemic. My child came home from university, and together with eight households, we formed a survival pod. In this network, made up of every kind of family blend you might be able to imagine–queer, trans, multiracial, multigenerational and multilingual–we relied on each other for care. But in both the immediate aftermath of Katrina and the long months of lockdown during the height of the pandemic, the way that we were able to access the resources the state made available for survival was determined by an idea of family that was limited to blood relations, households. Again, fear was a tool for the state to dictate isolation and encourage consumption. In the face of that, we chose to belong to a collective, to be together. And the state systems that were responsible for health, schools, employment, and food alleged that we needed to get back to normal, sowing seeds of convenience and individualism from masking policies to no longer making tests available to hoarding vaccines. We were once again regulated into individualism, into “just worry about yourself and what is yours.” It split so many of our realities.

Journal Entry

Friday, September 26, 2025

I feel cold when I try to remember. Small. I had just turned 33. My baby was four. We had adopted a kitten earlier that year. Our combined or “family” income was under $40,000 per year. I waited tables and worked in the library at the university where I was failing out of graduate school. I had just been given an old white Ford Taurus by my mom that I referred to as “the maxi pad.” It was one of the many things that we lost in the storm. There are too many things that we lost in the storm that don’t have a name. There is one thing that I lost in that storm that I’m thankful was ripped out of me forever: the last vestige of belief in the American dream, and eventually the investment in making my little family look like what that dream allegedly promised. We were tiny and fragile without our community and that was no dream.

I’m tired. Writing this essay makes me feel mad and ill and my hand hurts from writing. All this remembering and reading old journals made me go back to read the beginning of Naomi Klein’s The Shock Doctrine. After the introduction, where she talks about being in the shelter in Baton Rouge right after Katrina, she then interviews this older woman in Montreal, a shock therapy survivor. During the course of the interview, Klein, thinking that the woman has colored in the insides of empty cigarette boxes, realizes on closer inspection, “It is actually extremely dense, miniscule handwriting: names, numbers, thousands of words.” Part of me was stunned and perplexed when I read that, and another part of me was scared for her and also scared for me. Could that happen to me, that madness, from all the constant trauma? While I don’t understand how she did it, writing so minutely in those cigarette boxes, something about it also made sense to me. There was some kind of familiar logic to it. And there’s a way that I want to write this essay on the inside of my own mouth. Like the essay can’t possibly reveal the wound or its medicine, because it is written inside our collective flesh, and to see that flesh you would have to cut us open. Again. And some of us, we are just now, maybe, starting to think we can heal.