Co-lactation

Our baby has my partner’s smile, our donor’s lashes and hopefully, my gut flora.

My partner and I both wanted to chest-feed our baby once they were born. We believe, and studies show, that human milk helps build an infant’s immune system and thus plays a role in their epigenetic expression. As the “non-bio” parent, I was curious if this was one of the many ways my child could inherit something from me on a biological level.

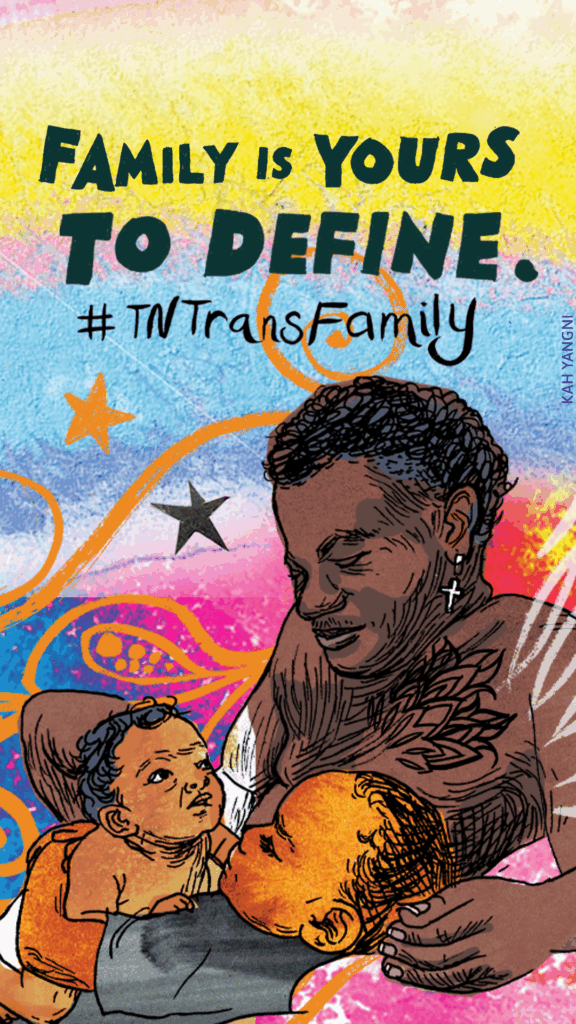

I’d been wrestling with the assimilationist in my head for a number of years that pushed me to construct family in a particular way. Over time, I grew more confident and the urge to assimilate dialed down. My partner, siblings and parents reminded me I descend from a long line of non-biological ancestors. I remembered that actually, we are related to everyone who helped our people survive. Despite the values I plan to instill in my child, the world is loud, influential, and commanding. Our colonized society has normalized culture and customs as biology. It says that relationships, gender, genes, and inheritance are static and unchanging from birth. We wanted to queer that.

There are protocols to help people make milk who didn’t give birth. This is great for adoptive parents, trans femme parents (Yes! Trans women + femmes can chest-feed!), and more. But most protocols don’t account for co-lactation — two people trying to feed one baby.

When reading Lactation For The Rest of Us, I was hoping to be inspired by stories of LGBTQ+ folks who made it work and to get some strategies. Not a single story on co-lactation ended how I wanted it to. Some folks had to accept they didn’t make much milk. Others did make milk, but it made the birthing parent incredibly jealous and so they stopped. I was beginning to stress out. Maybe that’s why the lactation consultants laughed when I said I’d love to do 50/50 feeding with my partner.

“That’s just not how it works,” I was told over and over by experts. My partner needed to establish her supply as the birthing parent. She would have to feed our baby just about every two hours, otherwise she could get pain in her chest from too much milk or not have “enough” milk. I still wonder about that last part. I wonder what “enough” means for someone who has a whole other person lactating. So much of the advice and expertise was based on folks trying to make milk solo. Lactation education relies on this core, patriarchal belief that newborn care is tasked to one person and is gendered work for “women,” which is what we wanted to challenge. At the time, we couldn’t find protocols for two people trying to feed at the same time (but here’s some case studies for you). And that translates into words that can scare you if you aren’t keenly aware. “Enough.” Who wants their newborn to starve?

“Enough?” I would ask myself when I stared at the 0.5 ounces I made after a full day of pumping every two hours. Before my kiddo arrived, I only compared myself against myself. My partner reassured me that it would be plenty for a newborn. Still, I knew I wasn’t doing “everything” I could have possibly done to increase my supply. You’re supposed to, according to the Newman-Goldfarb method:

- Take estrogen daily for one month. You can also take progesterone-only medication if you have a disability like me that makes you very susceptible to estrogen.

- Take domperidone every 4 hours for at least 3 months. Oh yeah, by the way, you have to get that shipped in from New Zealand, which took about two months. Order MORE THAN ENOUGH. You need enough to gradually wean yourself off of it, which can take weeks. If you quit suddenly, you’re at increased risk for mental health dips…Take it from me.

- Pump every two hours (including at night) for 10-20 minutes. It might take 1-3 months before milk appears. Luckily, I got milk the very first time I pumped.

- CRY. You gotta let it out. I added this one.

- Meditate. I was given the advice to think about milk flowing from you to your baby and it really helped. I hope it could help someone during the prenatal stage.

I guess that’s why I thought I “should” have made more, but I couldn’t keep up with the pumping regimen. My partner needed more support as the pregnancy went on. After work, I cooked, cleaned, and massaged her aching body with my own. On most weekends, I fixed things up around the house since we were going to birth at home. Most nights during the last trimester, we took birth hypnosis classes. My care team’s spirited encouragement made me feel like I couldn’t say it was too much. “If you want to make the time, you could,” was intended to be inspiring. Instead, I felt like I wasn’t enough, though I felt like I had given everything.

I’d spent the previous months in back-to-back IVF cycles, stabbing myself daily 3-4 times for almost 60 days. During that time, I had a cascading list of supplements to take to make “good” eggs for “good” embryos. I had also struggled to keep up with the medications for my autoimmune condition. Birthing was never something I wanted to do, but my disability solidified that life choice. There was a very high chance of the fetus having a hole in their heart and being stillborn. There’s a pregnancy group on Facebook for folks with my condition and it was filled with stories of loss and grief. Good enough. My body was in some ways “not.” The embryos had to be good enough.

When I was at my breaking point, I reached for some CBD to curb the nerve pain cramping my leg and keeping me up at night. Then I was told that I had ruined my milk and needed to dump it. No! Those 0.5 ounces meant the world to me. I labeled them as CBD milk and froze them. I would never give my baby that milk, but I thought it could have some other purpose. Human milk is truly magical like that. Eventually, I got a second opinion from two professionals that the CBD milk could be some good adult skincare cream. I felt a wave of relief. I started to wonder if I was the “skincare mom” and reimagine what “enough” milk could mean on my own terms.

My partner and I started referring to me as “snack mom” and worked with my lactation consultant to have a more realistic schedule for myself. I was not going to pump around the clock and was tired of feeling subpar because of it. A full supply was never my goal. I just wanted to connect with my child, share my immune system (I can introduce the foods my partner is allergic to through my breastmilk), and give my partner a break. Snack Mom was the language that clicked for our care team.

I pumped 4-6 times a day instead of 12. I reused one bag per day. Who in the world has time or the fridge space for a separate bag after each pump when inducing!? I took days off from pumping for the holidays.

The day kiddo was born, my partner was resting beside me in our bed getting sutured after nearly 46 hours of labor. Covered in blood, I comforted our exhausted, crying newborn by feeding them. They ate and ate and ate and fell asleep. It was more than enough.

Would I do it again? Yes. I do find a lot of joy in my milk being my child’s first meal. It was validating as a disabled person to influence my child’s epigenetics. We’re under a regime that seeks to erase me as a “non-biological” parent. I still have to fight to be seen as a legal parent, not because I want to assimilate to the state, but because my relationship with my child has no protections unless I do. And of course even that is temporal in this political climate. And so, queering biology, linking my child to my microbiome, creates an irrevocable connection. It resists biological essentialism — or the concept that westernized biology dominates our validity of family, personality, life expectancy, etc.

How? Well, this opens up an avenue for all sorts of relationships. Imagine besties, non-romantic co-parents, and other folks co-lactating. Imagine more milk banks across the country where folks can give their extra supplies to babies who need them. This exchange of immunity and genetic expression is powerful. Imagine a birthing person takes a lot of immune suppressants or has a lot of allergies; it would be such a help for the baby to have other sources of antibodies and gut flora. What else can you imagine?

To this day, 5 months postpartum, I still can give my kiddo a little snack while my partner is returning from the store or another room. I continue to adjust my goals and expectations. I am still Snack Mom, but kiddo has shown me so many other ways they need me. I am Comfort Mom when they are on my chest to sleep versus eat. I am Diaper Mom and we cry through the uncomfortable touch of cold wet wipes at 4 a.m. together. At 4 months, we started playing guitar in the mornings. Soon, they will be eating solids and Snack Mom will take on an all new meaning. The connection only grows from here no matter how much milk you make.